Social conditions concern the human communities in the Planning Area, including towns, cities, and rural areas, and the custom, culture, and history of the area as it relates to human settlement, as well as current social values.

This section discusses population and demographics, custom, culture, and social trends. For information on the history of human settlement in the Planning Area, see Section 3.7.1 Cultural Resources.

Population and Demographics

Table 3–53 provides a summary of population for the Planning Area counties in 1970 and 2009, and Table 3–54 provides information on population in individual towns in the Planning Area. The most populous county in the Planning Area is Park County, with nearly 28,000 residents. Big Horn County contains approximately 11,600 residents, Washakie County contains approximately 7,900, and Hot Springs County contains approximately 4,600. The most populous cities in the Planning Area, in order of decreasing population, are Cody (Park County), Powell (Park County), Worland (Washakie County), Thermopolis (Hot Springs County), and Lovell (Big Horn County).

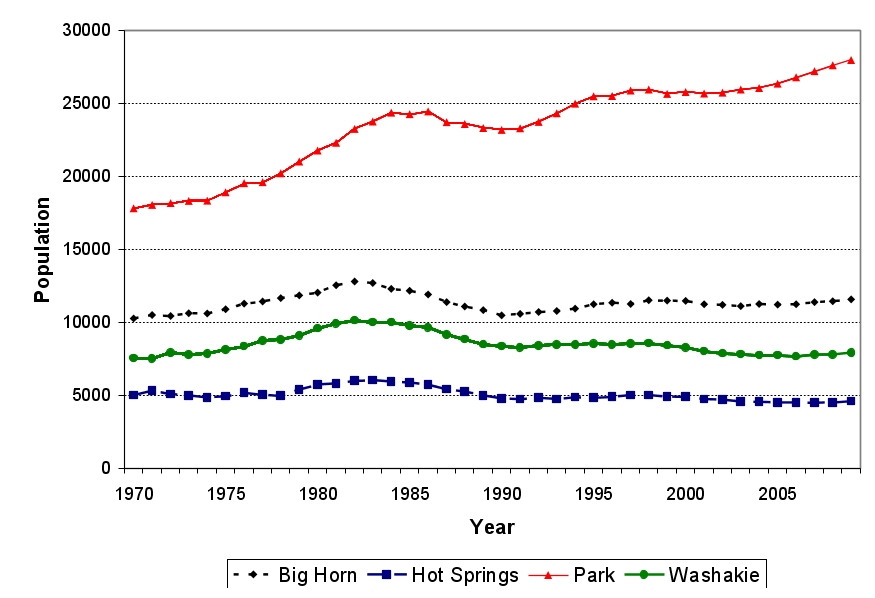

Figure 3-16 provides additional detailed trend information for county populations from 1970 through 2009. The figure shows population generally increased from 1970 to the early 1980s in all four counties within the Planning Area, then generally declined through the mid to late 1980s. In Park County, population has increased steadily from about 1990 to the present day. In Big Horn County, population has remained relatively constant during the same period. In Hot Springs and Washakie counties, population has decreased slightly from 1990 levels, particularly since the late 1990s.

Table 3.53. Population Change by County, 1970-2009

| Area | Population in 1970 | Population in 2009 | Change 1970-2009 | Average Annual Change 1970-2009 |

| Big Horn County | 10,264 | 11,581 | 13% | 0.31% |

| Hot Springs County | 5,023 | 4,590 | -9% | -0.23% |

| Park County | 17,805 | 27,976 | 57% | 1.17% |

| Washakie County | 7,557 | 7,911 | 5% | 0.12% |

| state of Wyoming | 333,795 | 544,270 | 63% | 1.26% |

| United States | 203,798,722 | 307,006,550 | 51% | 1.06% |

| Sources: BEA 2010a; US Census Bureau 2010a | ||||

Table 3.54. Population of Towns in 2000 and 2008

| Town | Population in 2000 | Population in 2008 | Change 2000-2008 | Average Annual Change 2000-2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Big Horn County | 11,461 | 11,310 | -1% | -0.2% |

| Basin | 1,243 | 1,239 | 0% | 0.0% |

| Burlington | 250 | 251 | 0% | 0.1% |

| Byron | 557 | 547 | -2% | -0.2% |

| Cowley | 560 | 607 | 8% | 1.0% |

| Deaver | 177 | 176 | -1% | -0.1% |

| Frannie1 | 209 | 209 | 0% | 0.0% |

| Greybull | 1,815 | 1,743 | -4% | -0.5% |

| Lovell | 2,361 | 2,266 | -4% | -0.5% |

| Manderson | 104 | 100 | -3% | -0.4% |

| Hot Springs County | 4,882 | 4,570 | -6% | -0.8% |

| East Thermopolis | 274 | 259 | -5% | -0.7% |

| Kirby | 57 | 54 | -5% | -0.6% |

| Thermopolis | 3,172 | 2,936 | -7% | -1.0% |

| Park County | 25,786 | 27,300 | 6% | 0.7% |

| Cody | 8,895 | 9,264 | 4% | 0.5% |

| Meeteetse | 351 | 346 | -1% | -0.2% |

| Powell | 5,367 | 5,414 | 1% | 0.1% |

| Washakie County | 8,289 | 7,860 | -5% | -0.7% |

| Ten Sleep | 304 | 316 | 4% | 0.5% |

| Worland | 5,289 | 4,968 | -6% | -0.8% |

| state of Wyoming | 493,782 | 529,630 | 7% | 0.9% |

| Sources: US Census Bureau 2000; Wyoming Economic Analysis Division 2008 1Includes portions of Frannie in both Big Horn and Park counties. | ||||

Table 3-55 presents information about the population distribution by various age groups in 2009. The table shows the median age was higher in all four Planning Area counties than in the state or nation, and was highest in Hot Springs County. The percentage of people aged 65 and over is higher in all four counties than the state or national average. However, in Big Horn and Washakie counties, the percentage of people under 18 was slightly higher than the national and state averages; in these counties, relatively low percentages of people aged 18 to 44 is reflected in the higher median age. In Hot Springs and Park counties, there is also a relatively low percentage of people under the age of 18, as well as a relatively low percentage of people aged 18 to 44.

Table 3.55. Age Distribution by County, 2009

| Area | Median Age | Percent of People by Age Category | ||||

| Under 18 | 18-24 | 25-44 | 45-64 | 65 and Over | ||

| Big Horn County | 40.0 | 26% | 8% | 22% | 27% | 17% |

| Hot Springs County | 48.8 | 20% | 7% | 18% | 31% | 24% |

| Park County | 43.0 | 21% | 9% | 22% | 31% | 17% |

| Washakie County | 41.8 | 26% | 8% | 20% | 29% | 17% |

| state of Wyoming | 35.9 | 24% | 11% | 26% | 27% | 12% |

| United States | 38.2 | 24% | 10% | 27% | 26% | 13% |

| Sources: US Census Bureau 2010b; US Census Bureau 2010c; US Census Bureau 2010d; US Census Bureau 2010e | ||||||

Table 3-56 shows the same data for the year 2000, which helps establish the trend over time. The year 2000 and 2009 comparison shows that the population in all four counties is growing older, with an increasing median age and the expected changes in each age category (a smaller proportion of people in the younger categories, and a larger proportion in the older categories, in 2009 compared with 2000). At the national level, an aging population can create economic problems such as how to fund Social Security; however, at the local level, an aging population does not necessarily create substantial problems. One concern would be that there would likely be an increased demand for hospital services; to the degree that people on fixed incomes contribute less to local tax revenues, this can create an imbalance of local government revenues and expenditures.

Table 3.56. Age Distribution by County, 2000

| Area | Median Age | Percent of People by Age Category | ||||

| Under 18 | 18-24 | 25-44 | 45-64 | 65 and Over | ||

| Big Horn County | 38.7 | 29% | 7% | 23% | 25% | 17% |

| Hot Springs County | 44.2 | 22% | 6% | 23% | 29% | 20% |

| Park County | 39.8 | 24% | 9% | 25% | 27% | 15% |

| Washakie County | 39.4 | 27% | 6% | 25% | 25% | 16% |

| state of Wyoming | 36.2 | 26% | 10% | 28% | 24% | 12% |

| United States | 35.3 | 26% | 10% | 30% | 22% | 12% |

| Sources: US Census Bureau 2009a; US Census Bureau 2009b; US Census Bureau 2010b; US Census Bureau 2010c | ||||||

Table 3-57 provides a summary of educational attainment in each county within the Planning Area in year 2000. The table shows that the percentage of high school graduates is comparable to the statewide level in all four Planning Area counties, and higher than the national average. Only Park County, however, has a level of four-year college graduates that equals or exceeds the state or national average.

Table 3.57. Educational Attainment in 2000

| Area | Percent of people age 25 and over: | |

| With a high school diploma | With a four-year college degree | |

| Big Horn County | 84% | 16% |

| Hot Springs County | 84% | 18% |

| Park County | 88% | 24% |

| Washakie County | 86% | 19% |

| state of Wyoming | 88% | 22% |

| United States | 80% | 24% |

| Source: US Census Bureau 2000 | ||

Table 3-58 shows data on gender distribution by counties. Gender distribution is very close to 50 percent male and 50 percent female in all four counties; Hot Springs County has the greatest difference, at 52 percent female and 48 percent male.

Table 3.58. Gender in 2000

| Area | Percent of people who are: | |

| Male | Female | |

| Big Horn County | 50% | 50% |

| Hot Springs County | 48% | 52% |

| Park County | 49% | 51% |

| Washakie County | 50% | 50% |

| state of Wyoming | 50% | 50% |

| United States | 49% | 51% |

| Source: US Census Bureau 2000 | ||

Because people of all ages and all levels of educational attainment, and both men and women, use BLM lands, the variation in these demographic groups is not a driver for BLM’s management actions in the Planning Area. However, the demographic data provides a backdrop of the human communities that will be affected by BLM’s decisions.

Transient and Seasonal Populations

Another demographic variable of interest relates to the transience and permanence of populations. Table 3-59 shows data from the 2000 Census on where people lived five years prior to the Census (i.e., in 1995). The data show the population of the study area counties is relatively stable: in all four counties, over half of the residents lived in the same residence five years prior, and about 75 to 80 percent of the residents lived in the same county. These percentages, which are comparable to state and national averages, show a substantial degree of stability in the population.

Table 3.59. Residence in 1995, as Tabulated in 2000

| Residence | Big Horn County | Hot Springs County | Park County | Washakie County | state of Wyoming | United States |

| Same house | 58% | 54% | 51% | 59% | 51% | 54% |

| Different house, same county | 19% | 21% | 23% | 20% | 24% | 25% |

| Different county, same state | 9% | 11% | 8% | 11% | 8% | 10% |

| Other location | 14% | 14% | 18% | 10% | 17% | 11% |

| Source: US Census Bureau 2000 | ||||||

The Wyoming Housing Database Partnership (WHDP 2009a) analyzed data from driver’s license exchanges to show the net movement of people into and out of the state. This data is more current than the Census data, and also shows the magnitude of net movements. The data account for people who transfer licenses from one state to Wyoming, and those who cancel their Wyoming license because they have moved out of state; however, it only tracks people with licenses, meaning that it does not include children. This analysis showed a net gain of about 42,000 people statewide from 2001 through 2009. The modal (i.e., most common) age bracket for in-migrants is between age 26 and 45. Driver’s license transfer data shows that most individuals are coming from other western states and Michigan, with California accounting for the single largest share (about 21 percent).

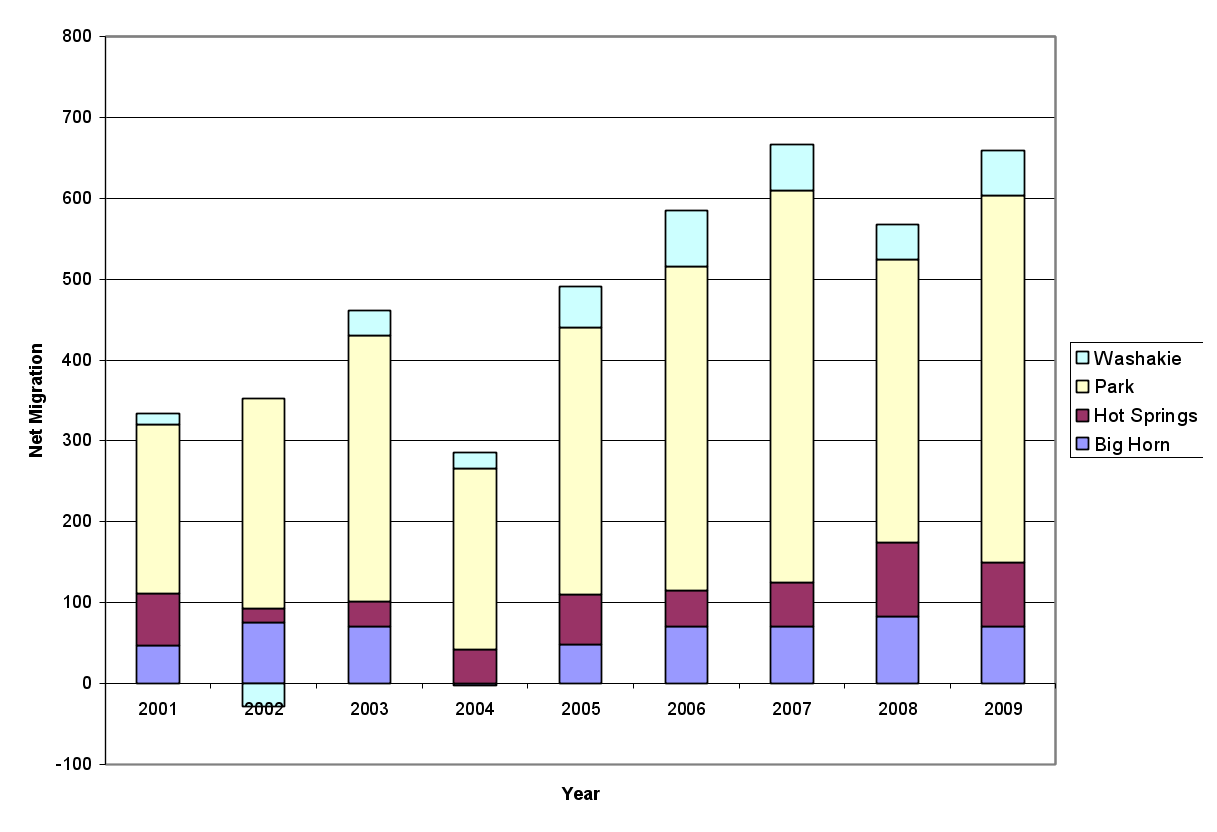

The Wyoming Housing Database Partnership analysis shows that the largest share of migrants to the state of Wyoming from 2001-2009 moved to places other than the Planning Area. The counties that received the largest share of migrants are Laramie (14 percent), Campbell (13 percent), Natrona (10 percent), and Teton (10 percent). By comparison, Park County received 7 percent of the migrants (about 3,000 people from 2001 through 2009), and Big Horn, Hot Springs, and Washakie Counties received between 0.7 and 1.3 percent each (534 in Big Horn, 484 in Hot Springs, and 313 in Washakie, for a total of about 1,300 people). Figure 3-17 shows the trend of migration over time.

Note: In 2002, net migration to Washakie County was negative. In 2004, net migration to Big Horn County was negative.

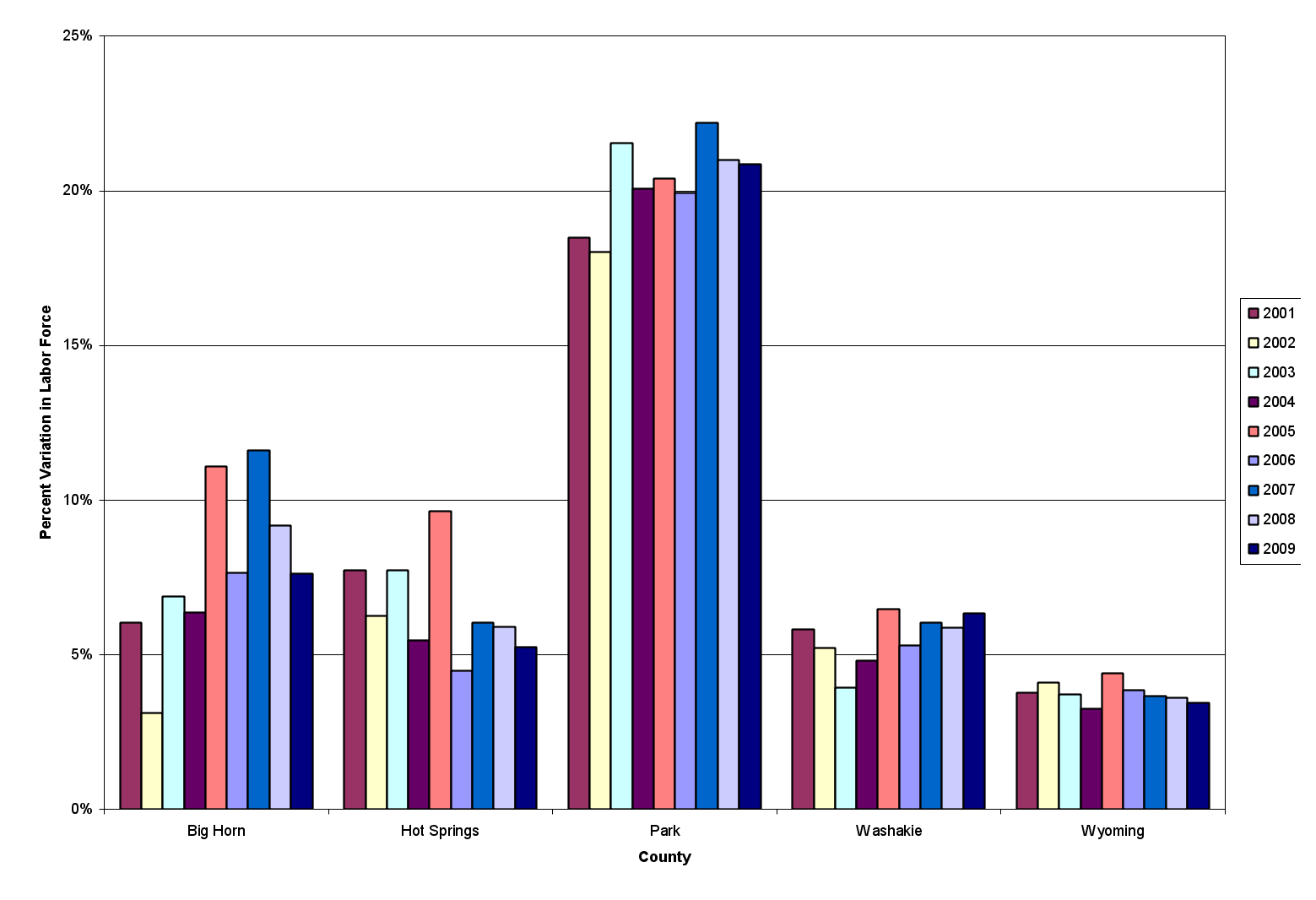

A common method for examining the degree of transience in the workforce is to analyze the variation in employment over a given year. If the size of the labor force (i.e., people with jobs or seeking jobs) does not change much over the year, this suggests the employment base is quite stable and few people move to the area on a temporary or seasonal basis to look for jobs. On the other hand, a relatively high magnitude of fluctuation in the labor force suggests an area undergoing change that is often marked by people moving temporarily from one area to another to seek employment.

Figure 3-18 shows the relative variation in the labor force for each county from 2001-2009. For each year and county, the values in the figure represent the difference in magnitude of the highest-month labor force versus the lowest-month labor force (“peak-to-trough”), divided by the average size of the labor force. For instance, in Park County in 2007, the labor force in the highest month (July) was 16,186, in the lowest month (January) was 13,013, and the average for the year was 14,288. Thus, the relative variation in the labor force in Park County in 2007 was (16,186 – 13,013) / 14,288, or about 22 percent of the labor force (BLS 2010a).

The figure shows that labor force fluctuations are greatest in Park County (between 20 and 22 percent of the labor force). Labor force fluctuations represent a smaller portion of the average labor force in Big Horn and Hot Springs Counties (typically five to ten percent) and Washakie County (about five percent). Labor force variations in Wyoming are typically on the order of three to four percent. Note, however, that the labor force variation at the county level includes people who move temporarily from one county to another seeking work (e.g., people who move from Laramie County to Park County seeking summer work would be included in the Park County labor force fluctuation, but not the statewide labor force fluctuation). For this reason, county-level variation is almost always greater than state-level variation.

Together, the three data sources presented above indicate that the residential population is quite stable, with about 75 to 80 percent of people who lived in the counties in 2000 having lived within the same county for at least five years. The Planning Area seems to attract net in-migration based on the driver’s license exchange data, with Park County attracting the most by far. Seasonal variation in the labor force is largest in Park County and somewhat smaller in the other three counties. Because the highest labor force occurs in the summer months and the lowest in the winter months, it is reasonable to assume that most of the summer-month additional employment is related to outdoor work, either directly (e.g., outdoor guides) or indirectly (e.g., hotel workers supported by increased tourism). BLM management actions that affect the quality of and access to recreational resources, livestock grazing, and oil and gas development areas therefore will affect the transient workforce as well as the permanent residents within the Planning Area.

A high proportion of transient workers can have both beneficial and adverse effects on the social fabric of a community. Transient workers pay local sales taxes when they purchase goods and services, and help local business people by providing both a temporary workforce when needed and a consumer base for retail activity. They also fill rental housing, which helps landlords. However, transient workers can also contribute to social instability. If BLM actions were to contribute to an increase or reduction in the size of the transient workforce, whether this would be viewed as a beneficial or adverse impact would depend on individual perspective. Similarly, the fact that Park County is gaining population and attracting substantial in-migration is likely viewed as beneficial by some residents and adverse by others.

Custom, Culture, and Social Trends

This section describes the social development, culture, and history of the Planning Area to provide insight into how changes to the Planning Area might affect the livelihood and quality of residential life. The section addresses the history of human settlement in the Planning Area, with a particular focus on economic and social development; land use plans within the counties, focusing on issues the counties have identified that relate to new or planned infrastructure; and “non-market” economic and social values.

Economic and Social History

Throughout the history of the Planning Area, the use of natural resources on private, state, and federal land has provided the basis for continued social and economic stability in all four counties. Agriculture, mining, mineral development and production, and tourism are directly tied to the ability to use federal and state land. As a result, management decisions for federal (and state) land and natural resources will have a ripple effect throughout the social and economic climate of the Planning Area. See Section 3.5 Heritage and Visual Resources for more information regarding the history and development of the Planning Area.

County Land Use Plans and Population Forecasts

All four counties in the Planning Area have comprehensive land use plans that address existing and planned or hoped-for future conditions of community infrastructure and other elements. The land use plans for the counties contain abundant information about policies and goals affecting development of industrial, residential, and commercial infrastructure, but they all generally support the continuation of balanced economic development along with the preservation, to the degree possible, of natural landscapes, wildlife habitat, and open space (Hot Springs County 2002; Hot Springs County 2005; Big Horn County 2009; Washakie County 2004; Park County 1998).

The Hot Springs County plan notes a number of issues related to present and future desired infrastructure, including the need to develop an industrial park and a new airport to attract greater diversity of industries (Hot Springs County 2005). The plan also expresses concern about growing federal and state regulation, including on public lands, that may slow or hinder economic development. The plan also specifically identifies several needs for new or improved public infrastructure. These include improved hospital services, motivated partly by the need to ensure that the aging county population has access to excellent health care; enhancement of highways to promote recognition of historical and cultural landmarks (although the plan notes that the physical condition of government roads in the county is generally excellent); improved public transportation; and the development of a new airport, funded substantially by state and federal contributions (Hot Springs County 2005).

The Big Horn County plan, which was adopted in January 2010, suggests that the county’s physical infrastructure is generally adequate for the relatively slow pace of development that the county expects in the near future. For instance, discussing water supply and distribution infrastructure in detail for each of the county communities, the plan concluded that while localized problems such as undersized or antiquated water lines can hamper development in specific locations, overall supplies are adequate for the future (Big Horn County 2009). Similarly, the plan notes that electricity, high-speed internet, telephone, and cable television are available for every incorporated community, though not for all homes in unincorporated areas. The plan does note the need to protect its agricultural industry, for instance by adjusting county land use programs and policies to support sustained agricultural profitability. The plan notes an increase in the number of hobby farms and ranchettes and notes that these operations may not have the same level of profitability of larger operations, and may compete with larger operations for the same land and water resources. However, the plan notes, these operations do contribute to the agricultural character of the county (Big Horn County 2009). The Big Horn County land use plan also identifies a need to diversify the region’s economy, as it relies relatively heavily on mining and public sector activities: education, government, and health care (Big Horn County 2009).

Infrastructure needs identified in the Washakie County land use plan include several transportation related improvements, such as improvement of the Worland airport and upgrades to U.S. Highway 16; improved health care facilities; enhanced infrastructure for recreational opportunities; and improved infrastructure to accept the increasing amount of septic waste, due to increased residential construction in unincorporated areas. The plan also describes the recent history of the county’s development, noting that the boom years of the late 1970s and early 1980s brought a steady increase in per capita income, and a number of rural subdivisions were laid out in response to the County’s rapid growth. Since the boom years, the county’s growth has been slower and the county has especially lost population between the ages of 25-34, which has resulted in lower school enrollment levels as well as an increasingly aging population. This aging demographic, along with other trends, has resulted in static home values, which also affects the local tax base (Washakie County 2004).

The Park County plan focuses primarily on goals and policies related to planning and, compared to the other county land use plans in the area, does not have as great a focus on identifying specific needs for physical infrastructure. However, the Park County plan does identify some key policies as being important for future planning, such as the revision of subdivision procedures and standards to facilitate minor subdivisions (i.e., those smaller than 35 acres). The plan also recommends various policies to promote the county’s assets, such as incentives to developers to design projects that preserve scenic views (Park County 1998).

Understanding land use plans in the counties is important for BLM’s decision making in the RMP process, in part because federal law (43 CFR 1610.3) requires the BLM to prepare plans that are consistent with officially adopted local land use plans, identify inconsistencies with proposed BLM plans and local plans to the Governor, and take practical steps to resolve conflicts between federal and local plans. These requirements apply only if local governments notify BLM that a local land use plan has been adopted.

The Wyoming Economic Analysis Division (Wyoming Economic Analysis Division 2008) provides forecasts of population for Planning Area counties and some towns (Table 3–60). The data suggest that Park County will grow faster than the other counties in the Planning Area, and Big Horn will grow second fastest; however, both counties are projected to grow more slowly than the state overall. The Wyoming Economic Analysis Division forecasts that Hot Springs and Washakie Counties will lose population in future years.

Table 3.60. Population Forecasts through 2030

| Area | Population (Actual or Forecasted) | Change 2008-2030 | ||||

| 2000 | 2008 | 2020 | 2030 | Overall | Average Annual | |

| Big Horn County | 11,461 | 11,310 | 11,240 | 11,650 | 3% | 0.1% |

| Basin | 1,243 | 1,239 | 1,231 | 1,276 | 3% | 0.1% |

| Burlington | 250 | 251 | 249 | 259 | 3% | 0.1% |

| Byron | 557 | 547 | 544 | 564 | 3% | 0.1% |

| Cowley | 560 | 607 | 603 | 625 | 3% | 0.1% |

| Deaver | 177 | 176 | 175 | 181 | 3% | 0.1% |

| Frannie1 | 209 | 209 | 209 | 217 | 4% | 0.2% |

| Greybull | 1,815 | 1,743 | 1,732 | 1,796 | 3% | 0.1% |

| Lovell | 2,361 | 2,266 | 2,252 | 2,335 | 3% | 0.1% |

| Manderson | 104 | 100 | 100 | 103 | 3% | 0.1% |

| Hot Springs County | 4,882 | 4,570 | 4,450 | 4,420 | -3% | -0.2% |

| East Thermopolis | 274 | 259 | 252 | 250 | -3% | -0.2% |

| Kirby | 57 | 54 | 53 | 52 | -3% | -0.2% |

| Thermopolis | 3,172 | 2,936 | 2,859 | 2,840 | -3% | -0.2% |

| Park County | 25,786 | 27,300 | 28,270 | 29,860 | 9% | 0.4% |

| Cody | 8,895 | 9,264 | 9,593 | 10,133 | 9% | 0.4% |

| Meeteetse | 351 | 346 | 358 | 378 | 9% | 0.4% |

| Powell | 5,367 | 5,414 | 5,606 | 5,922 | 9% | 0.4% |

| Washakie County | 8,289 | 7,860 | 7,710 | 7,690 | -2% | -0.1% |

| Ten Sleep | 304 | 316 | 310 | 309 | -2% | -0.1% |

| Worland | 5,289 | 4,968 | 4,873 | 4,860 | -2% | -0.1% |

| state of Wyoming | 493,782 | 529,630 | 578,730 | 621,160 | 17% | 0.7% |

| Source: Wyoming Economic Analysis Division 2008 1 Includes portions of Frannie located in Big Horn and Park Counties. | ||||||

Non-Market Economic and Social Values

Consistent with the social, economic, and cultural development of the area, many residents of the Planning Area continue to place high value on the open spaces and vistas, continuing operation of farms and ranches, livestock grazing, and the wide variety of recreational opportunities available in and near the Planning Area. Based on the information in county land use plans as well as the scoping comments the BLM has received during the RMP revision process, the value of these features may not be fully represented in the marketplace. There is thus a reasonable argument for the consideration of “non-market values” in the analysis. Well established in economic theory, non-market values refer to the “utility” or “happiness” that people obtain from tangible or intangible goods or services, but that is not reflected in the market price of those goods or services. Non-market values include some forms of direct use – whether consumptive, such as recreational fishing and hunting, or non-consumptive, such as hiking, boating, wildlife viewing, and viewing scenic vistas. Non-market values also include “indirect” values, such as ecosystem services that support ecological resources, and “non-use” values, which include altruistic values (for others’ enjoyment), bequest values (for the ability of future generations to use the resource), and existence values (satisfaction from knowing that a resource exists, independent of any predicted use of the resource by any human being).

The scoping comments from the RMP and EIS process suggest that non-market values are an important component of value for many residents of the Planning Area. Many individuals submitted comments suggesting that the BLM should prioritize actions that maintain open space, preserve unique landscapes, and protect scenic viewsheds. Several commenters mentioned specific areas and vistas, such as the McCullough Peaks area and the approach to the Big Horn Mountains through Ten Sleep, that are most important to them. At least two commenters specifically stated concerns about nighttime visibility, which they feel is being degraded due to development in all forms (industrial, urban, and rural) contributing light pollution and air emissions. Some individuals recommended that the BLM minimize industrial development on public lands, such as oil and gas drilling, so as to preserve archeological and paleontological resources, open space, road-less areas, WSAs, and sagebrush steppe environment – even as some of these people also acknowledged the direct economic benefits of such industrial development. Several individuals commented that livestock grazing contributes to various values such as open space, wildlife habitat, buffers between federal lands and developed areas, and the traditional image and heritage of the historic rural landscapes of Wyoming and the Western United States. All of these comments can be considered as statements indicating non-market values that people hold.

In the context of the RMP and EIS, non-market values are implicitly included in the decision making context in the sense that market economic considerations, such as employment and tax revenues, are just one element affecting the development of the RMP alternatives, including the Agency Preferred Alternative. The RMP and EIS presents information about current conditions and potential impacts on a multitude of resources, including all of the resources that people value in a non-market context, such as open space, preservation and conservation of wildlife, and air quality. The present condition on these various resources, and the impacts on them from each of the alternatives, are evaluated within the RMP and EIS context, in concert with the analysis of market values as measured by employment, income, earnings, and tax revenues. Thus, although this RMP and EIS does not attempt to quantify the non-market values in dollar terms, the concepts that support non-market analysis – and the non-market values people hold – are built in to the RMP and EIS process and ultimately the development of the Proposed RMP.