3.2.2.2 Special Status Species and Natural Communities

Special status species are those species (plants, animals or fish) with populations that have declined to the point of substantial

Federal or state agency concern. Special status species include:

| • | Any species that is listed, is a candidate for listing, or is proposed for listing, as threatened or endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or National Marine Fisheries Service under the provisions of the Endangered Species Act |

| • | Any species designated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as a "listed," "candidate," "sensitive" or "species of concern," |

| • | Any species designated by each BLM state director as sensitive, a category that is normally used for species that occur on Bureau administered lands for which the BLM has the capability to significantly affect the conservation status of the species through management. |

| • | Any species which is listed by the State of Colorado in a category implying potential danger of extinction. |

Federally threatened and endangered species and designated critical habitat crucial to species viability are managed by the

USFWS in cooperation with other Federal agencies to support recovery. For listed species that have not had critical habitat

identified and designated, the BLM cooperates with the USFWS to identify and manage habitats to support the species.

The BLM also identified special natural communities within the D-E NCA, using information collected by the Colorado Natural

Heritage Program (CNHP). Special natural communities were defined as those that meet CNHP’s standards for exemplary, meaning

of high quality, or imperiled, meaning rare. A description of these natural communities is included within this section of

the DRMP.

The BLM planning team went through an extensive process to consider priority biological species and communities so that future

management could be based on an comprehensive understanding of species and habitat/vegetative community relationships. As

part of this process, the BLM identified vegetation/habitat types and species (plants or wildlife) that would be priorities

for management and would thus require special management consideration and attention. Seven vegetation/habitat types, covering

nearly all of the D-E NCA, were selected as priorities. Desert bighorn sheep and Colorado hookless cactus were identified

through this process as priority species, as they required special management consideration and attention beyond management

of their broader habitat types. For this reason, these two species are considered Priority Species in the section below, followed by all other special status species. Habitat for non-priority special status species, fish

and wildlife (including big game) are largely managed through management of the priority vegetation or habitat types listed

in this section.

After identifying the key attributes and associated indicators of health for each priority species and vegetation the planning

team established standards for each indicator so that its current condition could be summarized as “poor”, “fair”, “good”

or “very good”. The gap between current and desired condition were used to define objectives for management. Objectives were

focused particularly on key attributes that were determined to currently be in “fair” or “poor” condition. These indicators

should be considered additional to the Colorado Standards for Public Land Health, which the BLM is required to meet (or make

progress towards meeting) in the State of Colorado. For more detail on indicators, please see Appendix A.

This planning process is based on the “Planning for Priority Species and Vegetation” training offered by the BLM’s National

Training Center.

Desert Bighorn Sheep

The desert bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni), is a subspecies of bighorn sheep that occurs in seven states (CO, TX, CA, AZ, UT, NM, NV) across the desert Southwest regions

of the United States. Smaller than their Rocky Mountain cousins, desert bighorn sheep are well adapted to living in the desert

heat and cold. In contrast to deer and elk, bighorn sheep populations historically declined sharply during the early settlement

years of the West and have never recovered. Fewer than 80,000 sheep are believed to roam the west from Canada to Mexico, compared

to an estimated 1.2 million head of bighorn that existed at one time (Krausman and Shackleton 2000).

The Dominguez Canyon desert bighorn herd is currently estimated to be the second largest of four herds or bands in Colorado

(CPW 2012). Table 3.12 shows the most recent population estimates for Colorado’s desert bighorn herds (also see Map 3–11).

Table 19 Numbers of Desert Bighorn Sheep by Herd in Colorado

|

Hunting Unit |

Location |

Number |

|---|---|---|

|

S64

|

Upper Dolores River

|

70

|

|

S63

|

Middle Dolores River

|

45

|

|

S56

|

Black Ridge

|

200

|

|

S62

|

Uncompahgre (Dominguez)

|

160

|

| Source: George, Kahn, Miller, & Watkins 2009; updated through B. Banulis, personal communication, September 6, 2012, and S. Ducket, personal communication, September 6, 2012. | ||

All four Colorado bands were transplanted in from out-of-state populations. The Dominguez herd were released into the Big

Dominguez Creek drainage in 1983 (10 sheep from Arizona), 1984 (10 sheep from Arizona), and 1985 (21 sheep from Nevada in

two transplants). Additional sheep releases occurred in the Roubideau Creek drainage in 1991 (18 sheep from Arizona) and

1993 (20 sheep from Nevada). In 1995, 181 sheep were counted during a June helicopter survey. In the late 1990’s, the population

was estimated to be approximately 250 sheep. A Pasteurella pneumonia outbreak occurred in the population in 2001-2002. In 2001-2002 very few lambs were observed and the population

appeared to decline dramatically. Only 27 sheep (five lambs/100 ewes) were observed during the 2002 helicopter survey. The

population appeared to rebound in 2004 and 2005. In 2005, 100 sheep (69 lambs/100 ewes) were classified during coordinated

helicopter and ground surveys (Watkins 2005). Currently, the population is estimated at 160 individuals. This falls between

the middle to upper population goals for the herd established by Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

The BLM identified 3 sets of attributes and indicators to evaluate the health of desert bighorn sheep in the D-E NCA (Table

3.13). Although the herd’s current population size is rated as “good”, the D-E NCA’s desert bighorn sheep have a current rating

of “poor” for the potential for disease transmission due to overlap between desert bighorn sheep range and domestic sheep/goats.

Table 20 Attributes for Measuring the Health of Desert Bighorn Sheep

|

Attribute |

Indicator |

Data Source |

Condition Rating |

Rationale for Fair or Poor Condition Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Population structure and recruitment

|

Lamb to ewe ratio

|

Colorado Parks and Wildlife surveys

|

“Good”

|

Not applicable

|

|

Potential for disease transmission

|

Overlap of domestic sheep and goats with desert bighorn sheep

|

BLM and CPW GIS data

|

“Poor”

|

There is overlap between desert bighorn sheep range and domestic sheep allotments, as well as domestic goats

|

|

Population size

|

Five-year average of population size

|

CPW surveys

|

“Good”

|

Not applicable

|

| For more detail, see Appendix A, Planning for Priority Vegetation/Habitats and Species | ||||

Research has been rapidly evolving in regard to disease transmission between wild and domestic sheep. Most recently, research

conducted out of Washington State documented transmission in a field setting (Lawrence et al. 2010). Working groups have

formed periodically at national and regional levels to evaluate risks and develop management suggestions, often incorporating

both scientific experts as well as stakeholders affected by scientific conclusions and management recommendations. Because

the operating environment and exact mechanisms related to disease transmission in the field can be so complex and can require

detailed laboratory testing to prove definitively, most of these working groups have put substantial effort into deliberately

and carefully characterizing management conclusions related to disease, as well as the scientific research on which they are

based. As an example, the US Forest Service, the BLM Colorado State Office, Colorado Department of Agriculture, Colorado

Woolgrowers, and the Colorado Division of Wildlife (2009) signed a memorandum of understanding in 2009 that included the following

conclusions relating to disease:

| • | Contact between bighorn sheep and domestic sheep increases the probability of respiratory disease outbreaks in bighorn sheep |

| • | Not all disease outbreaks and reduced recruitment in bighorn sheep can be attributed to contact with domestic sheep |

The Wild Sheep Working Group of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies recently updated a series of management

recommendations designed to reduce the probability of interaction and disease transmission between wild and domestic sheep

(Wild Sheep Working Group 2012). These recommendations include proactive mitigation measures for land management agencies

and domestic sheep grazing operators.

Left unresolved is the identification of organisms that cause pneumonia in bighorn sheep, following contact with domestic

sheep (Wehausen, Kelley & Ramey 2011), possibly because of disease complexity (multiple pathogens) and limitations of research

tools applied. There is literature documenting pneumonia outbreaks and die-offs in bighorn sheep populations with no known

recent prior contact with domestic sheep (Goodson 1982). However, documented pneumonia epizootics are absent in the large

expanse of wild sheep range in Canada and Alaska where there have been almost no opportunity for direct or indirect contact

with domestic sheep, suggesting that interaction between domestic and wild sheep is a causal factor in the introduction of

these pathogens into wild sheep herds (Hoefs & Cowan 1979; Hoefs & Bayer 1983; Monello, Murray & Cassirer 2001; Jenkins, Veitch,

Kutz, Bollinger, Chirino–Trejo, Elkin, West, Hoberg, & Polley 2007).

When domestic and wild sheep or goats have opportunities to intermingle depending on proximity of domestic livestock to wild

populations of sheep, and when population trends indicate that disease may be a factor in a population, the risk of disease

transmission becomes a management concern. Domestic sheep and goats are present in the D-E NCA, making the risk of disease

transmission to wild sheep a management concern. There are currently five domestic sheep allotments within the D-E NCA, four

of which fall within desert bighorn sheep range (see livestock grazing section for more details). A Probability of Interaction

Assessment was conducted for livestock allotments to determine the likelihood of interaction between desert bighorn sheep

and domestic sheep on all allotments within the D-E NCA (see Appendix C). Of the 17 allotments in the D-E NCA, 8 were rated

as “medium probability” of interaction and 9 were rated as “high probability” of interaction using this assessment (Map 3–12).

The presence of domestic goats in Little Dominguez Canyon is a unique aspect of the Dominguez Canyon Wilderness due to the

continued occupancy of a homestead that was deeded to the BLM by Mr. Billy Rambo. He continues to maintain his residence

in the Wilderness under a “life lease” agreement, and has maintained a small flock of goats in the core area for the bighorn

sheep, since before the bighorns were introduced. Interaction between goats and wild bighorn sheep is a concern from a disease

transmission standpoint, because goats are not as “gregarious” (e.g., likely to group together) as some breeds of domestic

sheep. In addition, the lack of a herder or monitor makes would make it difficult to detect when intermingling occurs.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife has documented interaction between domestic goats and desert bighorn sheep in the Dominguez Canyon

Wilderness (Plank 2012, personal communication). Domestic sheep permittees within the D-E NCA have reported very little commingling

between desert bighorn sheep and domestic sheep within the D-E NCA. Domestic sheep grazing is a historical use of the D-E

NCA and such grazing was in existence prior to the initial transplants of bighorn sheep into the area in 1983. However, the

results of the model presented in Appendix C suggest the probability of interaction ranges from “medium” to “high” within

the D-E NCA.

Colorado Hookless Cactus

Colorado hookless cactus (Sclerocactus glaucus) was identified as a priority species for the D-E NCA, as it requires the BLM to identify special management beyond management

of its habitat. Listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, the Colorado hookless cactus was formerly called the

Uinta Basin hookless cactus. In 2009, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service determined that the Uinta Basin hookless cactus (S. glaucus) was three distinct species: S. glaucus, S. brevispinus, and S. wetlandicus (Federal Register, 74 FR 47112). The small, barrel-shaped cactus has straight spines (hence the name hookless) and pinkish-purple flowers.

Habitat for this species includes rocky hills, mesa slopes, and alluvial benches in desert shrub communities at elevations

from 4,500 to 6,000 feet (Lyon & Kuhn 2011). The Uinta Basin Recovery Plan estimated that 15,000 individual plants occur in

the Gunnison River population (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1990). Recent surveys conducted by the BLM near Delta, Colorado,

suggest total population size and distribution may be much larger than originally thought. In 2010, the US Fish and Wildlife

Service estimated that Colorado had a known population of 19,000 individuals of Colorado hookless cactus in Delta, Montrose,

Mesa and Garfield counties (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2010). One of two population centers is found on alluvial river

terraces of the Gunnison River from near Delta, Colorado to southern Mesa County, Colorado (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

2010). Although data collected by the BLM and CNHP show that there are 101 principal occurrences of S. glaucus in Colorado, 40 are within the D-E NCA.

In the most current Colorado Natural Heritage Program survey of D-E NCA for hookless cactus, all A-ranked occurrences are

in the Uncompahgre Field Office side of the D-E NCA, along the Escalante Road east of the Gunnison River, in Wells Gulch and

on McCarty Bench, west of the Gunnison River (Lyon & Kuhn 2011). B-ranked occurrences inside the D-E NCA include Leonard’s

Basin, Big Dominguez Creek and Cactus Park (Lyon & Kuhn 2011). The difference between A and B ranking is excellent versus

good viability.

Threats to the species within the D-E NCA include habitat degradation as a result of encroachment of non-native halogeton

and cheatgrass, off-road vehicle use, collection, as well as trampling and grazing by livestock. Predation by rabbits and

cactus-borer beetle (Moneilema semipunctatum) may also be a significant source of mortality (US Fish and Wildlife Service 2010). Additional studies are currently underway

to determine the long-term, population-level effects of livestock grazing on Colorado hookless cactus.

The BLM identified 3 sets of attributes and indicators for evaluating the health of Colorado hookless cactus populations in

the D-E NCA (Table 3.14). Two of these attributes are currently ranked as “good”. For population size, the current condition

rating is “fair” because of evidence of declining populations.

Table 21 Attributes for Measuring the Health of Colorado Hookless Cactus

|

Attribute |

Indicator |

Data Source |

Condition Rating |

Rationale for Fair or Poor Condition Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Habitat quality

|

Percent of sites with less than 10% relative cover of invasive plants

|

Colorado Natural Heritage Program specialist opinion

|

“Good”

|

Not applicable

|

|

Population structure and recruitment

|

Percent of populations with at least 5% of the population being small individuals

|

Colorado Natural Heritage Program specialist opinion

|

“Good”

|

Not applicable

|

|

Population size

|

Twenty year trend in number of individuals in known populations

|

Colorado Natural Heritage Program

|

“Fair”

|

The number of individuals is decreasing within multiple populations in the D-E NCA

|

| For more detail, see Appendix A, Planning for Priority Vegetation/Habitats and Species | ||||

Other Special Status Species

Plants

Within the D-E NCA, the distribution and presence of most of the special status species is known from Colorado Natural Heritage

Program inventories, project-related biological surveys, Land Health Assessments, and other information (Map 3–13). Seven special status plant species (6 BLM sensitive, 1 federally threatened) have either been documented or have suitable

habitat associated with the D-E NCA. The six BLM sensitive species (this excludes Colorado hookless cactus, a federally threatened

species that is described in the preceding subsection) are described below.

Habitat for the Grand Junction milkvetch includes sparsely vegetated sites, often within the Chinle and Morrison formations and selenium-bearing soils, in Pinyon-juniper

and sagebrush communities at 4,800 to 6200 feet in elevation. Plants often occur on rocky slopes and in canyons. Current knowledge

indicates that the species is confined to the east side of the Uncompahgre Plateau. According to the 2010 CNHP D-E NCA Rare

Plant Survey, ten populations are scattered in the Big and Little Dominguez canyons, Bar X Bench, Triangle Mesa and Escalante

Canyon. CNHP element occurrence is excellent and good.

Habitat for the Naturita milkvetch includes the cracks and ledges of sandstone cliffs and flat bedrock areas with shallow soil development, within Pinyon-juniper

woodlands at elevations of 5,000 to 7,000 feet. This species occurs on mesas adjacent to the Dolores River and its tributaries

in Montrose and San Miguel counties. Recent surveys have found additional populations in the Mesa County portion of the D-E

NCA, and the species appears to be more abundant than originally thought. There are two known Naturita milkvetch occurrences,

totaling approximately 100 individual plants within the D-E NCA. The highest ranking occurrence (Good) is in Unaweep Canyon.

The Eastwood monkey-flower occurs exclusively in hanging gardens in the shallow alcoves or horizontal cracks of sandstone canyon walls at 4,700 to 5,800

feet in elevation. Several subpopulations occur in a series of seep alcoves along Escalante Canyon. CNHP records indicate

there are approximately seven principal occurrences in the D-E NCA. All appear to be on the north slopes of Escalante Creek.

The majority of the occurrences are ranked A-ranked by CNHP. Bar X Bench, in the Wagon Park area also has a B-ranked population.

The Montrose bladderpod occurs in sandy-gravel soil comprised mostly of sandstone fragments over Mancos Shale adobe soils, primarily in Pinyon-juniper

woodlands or Pinyon-juniper and salt desert scrub mixed communities at 5,800 to 7,500 feet in elevation. The species occurs

less often in sandy soils in sagebrush steppe communities. Distribution centers are on the Uncompahgre River Valley in south

Montrose County and north Ouray County, with most occurrences near the town of Montrose. However, an outlying subpopulation

persists near Escalante Canyon just south of the Delta County line.

Habitat for Colorado desert parsley occurs in adobe hills and plains on rocky soils derived from Mancos Formation shale, primarily in shrub communities dominated

by sagebrush, shadscale, greasewood, or scrub oak communities at 5,500 to 7,000 feet in elevation. This species has not yet

been documented in the D-E NCA but has the potential to occur.

The Osterhout’s cryptantha occurs in reddish-purple decomposed sandstone, in barren dry sites. Elevation ranges from 4,500 to 6,100 feet. In Colorado

the species is limited to Mesa County, with the main populations centering on Rabbit Valley and Gateway. Although the species

has not been recorded within the D-E NCA, suitable habitat is present.

Reptiles

The following special status reptiles (all State species of concern and BLM sensitive species) occur or have the potential

to occur in the D-E NCA:

Longnose leopard lizards are found in stands of greasewood and sagebrush with a large percentage of open ground. The species has not been recorded

in the D-E NCA but is likely to occur in the lower elevations of the D-E NCA.

The midget faded rattlesnake has been recorded in the D-E NCA. Observations in the Grand Junction field office suggest the species is typically observed

in or near rocky outcrops.

The milk snake has not been recorded in the D-E NCA but has been recorded adjacent to the Gunnison and Colorado Rivers upstream and downstream

of the D-E NCA. The species utilizes a wide range of habitats and is likely to occur in the D-E NCA.

Amphibians

Three special status amphibian species occur or have the potential to occur in the D-E NCA. All three of these species are

both State species of concern and BLM sensitive species.

The canyon treefrog is largely restricted to riparian areas in rocky canyons. It is typically found along streams among medium to large boulders,

from desert to desert grassland and into oak-pine forests. It is found in rocky canyons throughout the D-E NCA. The species

is common in Escalante Canyon and in Big and Little Dominguez Canyons.

The Great Basin spadefoot occurs mainly in sagebrush flats, semi-desert shrublands, and pinyon-juniper woodland. This species digs its own burrow in

loose soil or uses those of small mammals, and it breeds in temporary or permanent water, including rain pools, pools in intermittent

streams, and flooded areas along streams. The species has not been confirmed in the D-E NCA but is likely to occur.

The northern leopard frog generally inhabits permanent water with rooted aquatic vegetation. The species has been observed along the Gunnison River

within the D-E NCA during surveys conducted in 2008.

Birds

There are 16 special status bird species that occur, or have the potential to occur, in the D-E NCA. These are described below.

The northern goshawk, a BLM sensitive species, is not known to occur on the D-E NCA. Most breeding habitat likely exists on National Forest Service

lands adjacent to the D-E NCA. Foraging may occur within the D-E NCA, especially during the winter. Breeding habitat in the

D-E NCA is generally marginal for this species and is likely restricted to isolated stands of ponderosa pine, Douglas fir

and aspen.

The western burrowing owl, a BLM sensitive species, has the potential to occur in active prairie dog towns in the D-E NCA, within the desert shrub/saltbush

vegetation type. The Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory conducted a burrowing owl study in the summer of 2008. No burrowing owls

were documented within the D-E NCA.

The Mexican spotted owl, a federally threatened species, occurs in southwestern Colorado and has never been recorded within the D-E NCA. Although

potential habitat for the species does occur in the D-E NCA, the closest designated critical habitat for the species occurs

approximately 30 miles southwest of the D-E NCA boundary in the San Juan Mountains of Utah.

Peregrine falcons, which are a BLM sensitive species, occur throughout Colorado. Much of the canyon habitat within the D-E NCA could be considered

potential nesting habitat. There are three known occurrences within the D-E NCA: Escalante Canyon, lower Dominguez Canyon

and Unaweep Canyon (Map 3–14).

The Golden eagle, protected under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, occurs throughout Colorado. Much of the canyon habitat within

the D-E NCA could be considered potential nesting habitat. Four territories are in the D-E NCA: McCarty Bench, Broughton,

Escalante Creek, and Dry Fork of Escalante (Map 3–14).

Bald eagles, which are protected under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act and area a BLM sensitive species, occur throughout western

Colorado during winter months. Winter concentration habitat (as mapped by Colorado Parks and Wildlife) is located along the

Gunnison River within the D-E NCA. Until recently, no known bald eagle nests were in the D-E NCA area. Several bald eagle

nests have been documented in the vicinity of Delta, CO, including one along the Gunnison River, just outside the D-E NCA

boundary (see Map 3–14).

Habitat for the ferruginous hawk, a BLM sensitive species, occurs within the D-E NCA in the desert shrub/saltbush vegetation type. The species has not been

observed in the D-E NCA.

Various species of migratory birds summer or winter in the D-E NCA, or migrate through the D-E NCA. The habitat diversity

provided by broad expanses of pinyon juniper, sagebrush, and saltbush vegetation zones support numerous species of birds.

Western Colorado, including the D-E NCA, is considered migratory habitat for the White-faced ibis and American white pelican. Breeding of these species has not been recorded in the D-E NCA.

Habitat for the western yellow-billed cuckoo, a Federal candidate for listing and BLM sensitive species, occurs along the Gunnison River within the D-E NCA. Yellow-billed

cuckoos have not been recorded in the D-E NCA. The Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory has recorded two sightings approximately

25 miles east and approximately 5 miles north of the D-E NCA. However, the species is difficult to detect and may migrate

through the area or remain in suitable cottonwood habitat within the D-E NCA. Breeding of yellow-billed cuckoos in the area

was confirmed along the North Fork of the Gunnison River.

The range of the Southwestern willow flycatcher, a federally endangered species, extends into southwestern Colorado but is not believed to include the D-E NCA. The species

has never been recorded in the D-E NCA and the USFWS no longer lists the species to occur in the D-E NCA, but potential habitat

exists in the Hunting Ground area.

The long-billed curlew, a State species of concern and BLM sensitive species, typically breeds in short grass and mixed-grasslands. Breeding has

also been recorded in croplands and desert grasslands northwest of Grand Junction. The species is not known to occur in the

D-E NCA, but potential habitat exists in the Hunting Ground area.

Brewer’s sparrow, a BLM sensitive species, is commonly associated with sagebrush shrublands and is likely to occur in sagebrush habitat within

the upper elevations of the D-E NCA.

The Black swifts, a BLM sensitive species, nests within close proximity to falling water on a cliff. They place nests in small cavities within

the spray zone or directly behind sheets of falling water. The D-E NCA provides a limited amount of potential nesting habitat

for the species in Big Dominguez and Escalante Creeks.

Columbian Sharp-tailed grouse, a BLM sensitive species, do not currently occur in the D-E NCA. Though portions of the D-E NCA are mapped as historic habitat

for the species, they are most commonly found in high elevation grassland areas interspersed with serviceberry, chokecherry,

oak brush, sagebrush, snowberry, and aspen. This habitat type is not found within the D-E NCA.

The Cactus Park area of the D-E NCA is mapped as historic range for the Gunnison sage-grouse, a Federal candidate for listing under the Endangered Species Act (Map 3–14). The Pinyon Mesa population of Gunnison sage-grouse occurs north of the D-E NCA. A conservation plan for this population

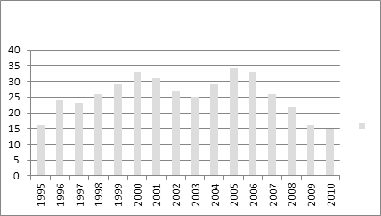

was completed in 2000. The number of males attending leks during annual lek counts of the Pinyon Mesa population has been

declining since 2005 (see Figure 3.2 below). This population was augmented in 2010 with grouse from the Gunnison area. These

birds were equipped with radio transmitters, and data obtained from these birds suggest the Cactus Park area of the D-E NCA

is currently used as wintering habitat for the Pinyon Mesa population of Gunnison sage-grouse (personal communication with

Neubaum, 2011). The BLM is managing for Gunnison sage-grouse habitat through management of the sagebrush shrublands vegetation

type. See Table 3.6 for current conditions of this vegetation type.

Figure 1 Pinyon Mesa Populations Male on Lek Count

Mammals

There are six special status mammal species that occur or are likely to occur within the D-E NCA. Note that information regarding

desert bighorn sheep, one of the six mammal species can be found in a separate subsection above.

White-tailed prairie dogs, a BLM sensitive species, are considered a keystone species within the desert shrub/saltbush vegetation and habitat type

in the D-E NCA. This habitat type is found in the lower elevations of the D-E NCA, primarily in the area known as the Hunting

Grounds, between the Gunnison River and US Highway 50 (Map 3–14). Currently the species is believed to occupy less than 10% of its suitable habitat in the D-E NCA, suggesting population

numbers are down likely as a result of disease and/or shooting by visitors to the D-E NCA.

Kit fox, also a BLM sensitive species, currently inhabit areas north of the town of Delta and have the potential to inhabit areas

of desert shrub/saltbush vegetation type in the Hunting Grounds area. However, the species has not been documented in the

D-E NCA.

Sensitive bat species are likely to utilize habitat throughout the area including snags, caves/crevasses and abandoned mines.

Of the sensitive bat species, Townsend’s big eared bats have been recorded along East Creek on the northern boundary of the

D-E NCA. Big free-tailed (Escalante Forks), Townsend’s big-eared (Escalante Forks; Escalante Boat Launch Bridge), and fringed myotis (Escalante Forks) bats have been captured or detected acoustically (Hayes, Ober, & Sherwin 2009).

Four other special status mammal species do not currently occur within the D-E NCA, but the D-E NCA contains either suitable

habitat or could provide a corridor for dispersal. These species are black-footed ferret, Canada lynx, Gunnison prairie dog

and North American wolverine.

Fish

There are eight special status fish species that occur or have the potential to occur in the D-E NCA. All of these species,

with the exception of the greenback cutthroat trout, are warmwater fish species. These warmwater fish currently inhabit

or historically inhabited the Gunnison River and the lower reaches of tributary creeks within the D-E NCA.

Bonytail, a federally endangered species, likely reside within the D-E NCA within the Gunnison River. Bonytail are a larger main-stem

river fish that prefer pool and eddy habitats. It is thought that flooded bottomland habitats are important growth and conditioning

areas for the species, particularly as nursery habitats for young. Threats include streamflow regulation, habitat modification,

predation by non-native fishes, pesticides and pollutants.

Humpback chub, a federally endangered species, are not know to occur within the D-E NCA. The nearest known population is downstream near

the Colorado-Utah border on the Colorado River. However, they are addressed in this RMP because they would be impacted by

management actions that result in water depletions. They are a large main-stem river fish that prefer deep, swift, canyon-bound

regions of the larger rivers within the Colorado River Basin. Adults require eddies and sheltered shoreline habitats maintained

by high spring flows. Young require low velocity shoreline habitats, including eddies, and backwaters, which are more prevalent

under base flow conditions. Threats include streamflow regulation, habitat modification, predation by non-native fishes,

pesticides and pollutants.

Razorback sucker, a federally endangered species, reside in the D-E NCA within the Gunnison River and have been collected periodically during

sampling efforts. The D-E NCA is within Designated Critical Habitat for this species. Razorbacks prefer warmwater reaches

of large rivers within the Colorado River Basin. Adults require deep runs, eddies, backwaters, and flooded off-channel environments

in spring; runs and pools often in shallow water associated with submerged sandbars in summer; and low velocity runs, pools,

and eddies in winter. Young require nursery environments with quiet, warm, shallow water such as tributary mouths, backwaters,

or inundated floodplain habitats. Threats include streamflow regulation, habitat modification, competition with and predation

by non-native fish, pesticides and pollutants.

Colorado River cutthroat trout, a BLM sensitive species, currently reside in portions of higher elevation coldwater reaches of select tributary streams

in the D-E NCA. Recent genetic research has revealed new information on the status and distribution of native cutthroat trout

species across Colorado (Metcalf, Love, Kennedy, Rogers, McDonald, Epp, Keepers, Cooper, Austin, and Martin 2012). The USFWS,

CPW, and the scientific community are working together to clarify the genetic status of cutthroat trout populations in western

Colorado. Current research shows that greenback cutthroat trout, a federally threatened species, were never found in the

D-E NCA. Cutthroat trout residing in portions of higher elevation coldwater reaches of select tributary streams in the D-E

NCA are most likely Colorado River cutthroat trout.

CPW and the U. S. Forest Service are currently moving forward with a reclamation project on Big Dominguez Creek upstream of

BLM lands within the D-E NCA. They are planning to replace non-native rainbow trout with native cutthroat trout (most likely

Colorado River cutthroat trout). It is likely that these fish will naturally distribute downstream into suitable habitats

on BLM reaches of the creek within the D-E NCA. Cutthroat trout require cold, clear, well oxygenated water with a good mix

of pool, riffle, and run habitats. Adults spawn in the spring and need clean gravel in which to lay eggs. They feed on a

variety of stream and terrestrial insects.

Greenback cutthroat trout, a federally threatened species, does not currently reside in the D-E NCA planning area. However, on the basis of recent

sampling and genetic work regarding the distribution of this subspecies, it is likely that this species was once found in

portions of higher elevation coldwater reaches of select tributary streams within the D-E NCA. Colorado Parks & Wildlife

and the U. S. Forest Service are currently moving forward with a reclamation project on Big Dominguez Creek upstream of BLM

lands within the D-E NCA. They are planning to replace non-native rainbow trout with pure lineage greenback cutthroat trout.

It is likely that these fish will naturally distribute downstream into suitable habitats on BLM reaches of the creek within

the D-E NCA. This species requires cold, clear, well oxygenated water with a good mix of pool, riffle, and run habitats. Adults

spawn in the spring and need clean gravels in which to lay eggs. They feed on a variety of stream and terrestrial insects.

Colorado pikeminnow, a federally endangered species, reside within the D-E NCA within the Gunnison River and have been periodically collected

during sampling efforts. The D-E NCA is within Designated Critical Habitat for this species. Colorado pikeminnow prefer

larger river habitats but are known to use smaller tributary streams throughout the Colorado River Basin. Adults require

pools, deep runs, and eddies maintained by high spring flows. Young require nursery habitats including backwaters that are

restructured by high spring flows and maintained by relatively stable base flows. Threats include streamflow regulation,

habitat modification, competition with and predation by non-native fishes, pesticides and pollutants.

Roundtail chub, a BLM sensitive species, reside primarily within the main-stem Gunnison River within the D-E NCA. However, adults use the

warmwater, lower elevation portions of the larger tributary streams (Cottonwood Creek, Escalante Creek, lower Big Dominguez

Creek, Kannah Creek) during the spring as spawning areas. Some adults may reside in the larger tributary streams year round.

Young use the smaller streams as nursery habitats before generally returning to the mainstem Gunnison River. This species

prefers runs, eddies, and deep complex pool systems with cover including woody debris and rocks. They feed on a variety of

aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates.

Bluehead sucker,a BLM sensitive species, reside in the Gunnison River and the warmwater lower elevation portions of the larger tributary

streams within the D-E NCA. Adults use the tributary streams for spawning and adult populations may exist in the larger tributaries

year round. Bluehead sucker prefer warm to cool streams with rocky substrates. Adults use deeper pool habitats with good

cover, whereas young prefer near shore, low velocity habitats. They eat algae, detritus, plant debris, and some aquatic insects.

Flannelmouth sucker, a BLM sensitive species, reside in the Gunnison River and the warmwater lower elevation portions of the larger tributary

streams within the D-E NCA. Habitat includes deep pools, deep runs, and riffles with gravel, rock, sand, or mud substrates.

Adults prefer deeper riffles and runs, whereas young prefer quiet, shallow riffles and near shore eddies. They feed on algae,

detritus, plant debris, and aquatic insects.

Special Natural Communities

The Colorado Natural Heritage Program (CNHP) collects information regarding rare and high quality vegetative communities,

in addition to information collected regarding rare species. For the purposes of this DRMP, the BLM defined unique vegetative

communities to be those that meet CNHP’s standards for exemplary communities, meaning of high quality, or imperiled communities,

meaning rare. Ancient vegetation is also considered for the purposes of this DRMP to be a special natural community. Imperiled

communities fall into one of three categories: critically imperiled, imperiled or vulnerable. Although these vegetative communities

are not special status species, they are included within this section of the DRMP.

Within the D-E NCA, four exemplary natural communities are currently documented in the most recent CNHP report (see Table

3.15). Two of these communities are riparian vegetation communities (those in Cottonwood Canyon and Big Dominguez Canyon),

one community is associated with natural seeps in the walls of Escalante Canyon, and one is an exemplary desert shrub community

in Rattlesnake Gulch. The hanging gardens within Escalante Canyon are also considered imperiled or vulnerable.

Table 22 Exemplary and Imperiled Native Vegetation Communities in the D-E NCA

| General Location | Natural Community Type | Quality Status | Rarity Status |

| Cottonwood Canyon | Narrowleaf cottonwood/skunkbush | Exemplary | Not imperiled |

| Upper Big Dominguez Canyon | Cottonwood riparian forest | Exemplary | Not imperiled |

| Rattlesnake Gulch | Cold desert shrublands | Exemplary | Not imperiled |

| Escalante Canyon | Hanging gardens | Exemplary | Imperiled |

| Ninemile Hill | Juniperus osteosperma/Hesperostipa comata wooded herbaceous vegetation | Not exemplary | Critically imperiled |

| Lower Sawmill Mesa | Juniperus osteosperma/Hesperostipa comata wooded herbaceous vegetation | Not exemplary | Critically imperiled |

| Escalante Canyon | Juniperus osteosperma/Hesperostipa comata wooded herbaceous vegetation | Not exemplary | Critically imperiled |

| Source: Colorado Natural Heritage Program 2011 | |||

An inventory of ancient vegetation in the D-E NCA has not been completed. It is likely that some stands of ancient pinyon-juniper

woodlands can be found in the higher elevations of the D-E NCA.