M.3 Affected Environment and Environmental Consequences

The following sections describe the environmental consequences that would occur due to hardrock mineral leasing in Alternative

D. There would be no impacts associated with hardrock mineral leasing under Alternative A (No Action Alternative), Alternative

B, or Alternative C. Therefore, these alternatives are not discussed any further.

M.3.1 Assumptions for Analysis

This section describes the assumptions used for analysis of impacts and the level of exploration and development that is reasonably

foreseeable during the life of the plan in Alternative D.

M.3.1.1 Alternative D

The following information is summarized from the Eastern Interior RMP Reasonably Foreseeable Developments for Locatable Minerals and Leasable Hardrock Mineral Resources in

the White Mountains Subunit (BLM 2012b) which is incorporated by reference. In the reasonably foreseeable development scenario (RFD) the BLM developed

models for typical suction dredging, small placer, and large placer operations, describing acres of annual disturbance, size

of the crew, hours of operation, fuel requirements, and type of equipment used for each type of operation. These same models

were used for the analysis of hardrock mineral leasing. This analysis assumes that development under mineral leases would

occur in a similar manner to development under the 3809 regulations (43 CFR 3809).

In accordance with the regulations for hardrock leasing (43 CFR 3500), the BLM envisions the following potential developments:

| 1. | The BLM would offer competitive leases for known deposits of placer gold in areas with high development potential (64,000 acres). |

| 2. | In the areas of known deposits of placer gold with medium development potential (85,000 acres), the BLM could issue exploration licenses based on public interest, likely leading to additional placer leases. |

| 3. | The BLM could issue exploration licenses based on public interest in the Roy Creek known REE deposit (11,000 acres). It is unlikely that any lode mineral occurrences explored under a license would move to a production lease within the anticipated twenty-year life of this plan. |

Methodology for Estimation of Mining Activities

To estimate the types and number of mining-related activities that might occur in the White Mountains if known mineral deposits

were made available for leasing, the BLM compared State of Alaska land of a similar nature in the Steese Subunit. For every

7,000 acres of state land in the Steese, there is one typical placer operation. There is one suction dredge operation for

every six miles of dredgable stream on high development potential areas of the Steese. These ratios are applied to areas of

known mineral deposits in the White Mountains NRA to establish the number of anticipated mechanical placer mining leases,

suction dredge leases, and both REE and placer exploration licenses over the life of this plan (Tables 3.1 and 3.2). Tables

3.1 and 3.2 include only acreage that can be directly estimated. Surface disturbance due to access routes was not estimated.

Access Assumptions

In order to reduce impacts, access would generally be limited as follows:

| • | Helicopter access for exploration licenses in the Roy Creek REE deposit; |

| • | No construction of roads for exploration licenses; |

| • | Winter overland moves for heavy equipment; |

| • | Summer access by all-terrain vehicle (ATV), consistent with off-highway vehicle (OHV) designations for Alternative D (limited to 1,000 pounds curb weight and 50 inches width). The BLM could approve heavier vehicles, such as utility terrain vehicles (UTV), on a case-by-case basis. The BLM would determine access routes to mining locations off current BLM-managed recreational trails on a case-by-case basis. Seasonal restrictions may apply; |

| • | Aircraft (helicopter or fixed-wing); and, |

| • | The BLM could consider construction of new access roads for placer development on a case-by-case basis if consistent with recreation management objectives and if other access was not feasible. The BLM estimates up to 20 miles of roads could be built over the life of the plan. |

Leases

The BLM may issue a competitive lease on unleased lands where a known valuable mineral deposit exists. This lease is accomplished

through a competitive lease sale. There are two types of leases applicable to hardrock mining in the White Mountains NRA,

and they are described in more detail below.

Suction Dredge Placer Leases: In addition to the mechanical operations described below, the BLM estimates there would be 10 suction dredge operations on

lands with high placer development potential and one additional operation on lands with medium development potential. A suction

dredge operation is limited to within active steam margins and would disturb about one-half acre per year. The maximum potential

disturbance from all 11 operations for the twenty-year life of the plan with natural concurrent reclamation is 84 acres.

Mechanized Placer Leases: To estimate the effects of development of traditional placer mining operations, the BLM considered two mining models: a smaller

mobile placer operation using a small dozer and excavator feeding an 11 cubic yard-per-hour washplant and a larger 145 cubic

yard-per-hour “Kantishna-type” washplant supported by a larger excavator and track-dozer. A small operation would mine and

reclaim one acre per year, but have a continual 4.4 acres of disturbance per year for a total disturbance of 27 acres for

the life of this plan. A large operation would have a continual 20 acres of disturbance and a total disturbance of 107 acres

over the life of this plan. The BLM estimates there could initially be two large and eight small operations annually, with

an additional three small operations following work done under exploration licenses, for a total disturbance of 507 acres

over the life of the plan.

Exploration Licenses

An exploration license allows the applicant to explore known mineral deposits to obtain geologic, environmental, and other

pertinent data concerning the deposits. The application for an exploration license includes an exploration plan approved by

the BLM that becomes part of the license. The requirements for an exploration plan are described in 43 CFR 3505.45. A proposed

notice of exploration must be published, inviting others to participate in the exploration under the license on a pro-rata

basis. Applications for exploration licenses would be subject to site-specific analysis under the National Environmental Policy

Act (NEPA). Site-specific measures to protect the environment and use for recreation would be included in the approved exploration

license. There are two types of licenses applicable to hardrock mining in the White Mountains NRA, and they are described

in more detail below.

Placer Exploration Licenses: The BLM may require exploration of placer resources in the medium development potential areas prior to issuing placer leases;

the applicant may request exploration licenses in the higher development potential areas before the BLM offers competitive

leases. Most placer exploration would cause minimal disturbance, but the applicant could also request approval for more intensive

placer sampling with heavy equipment. The BLM anticipates there could be four exploration licenses (5,000 acres each) requested

within the lands opened to leasing, resulting in direct disturbance to and reclamation of 20 acres over the life of the plan.

Rare-Earth Element Exploration Licenses: If the White Mountains NRA were opened to hardrock leasing, there would likely be an exploration license request for the

11,000 acres in the Roy Creek REE known deposit. Exploration activities would range from field mapping and sampling, to trenching

and core-drilling. The total life-of-plan disturbance from exploration of the Roy Creek REE deposit is expected to be 50 acres.

Anticipated Activity Due to Hardrock Leasing in the White Mountains Under Alternative D

| Activities under Reasonably Foreseeable Exploration and Development | High Potential Lands – Gold | High Potential Lands - REE | Medium Potential Lands – Gold | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Suction dredge placer leases | 10 leases | 1 lease | 11 | |

| Life of plan disturbance due to suction dredging (active stream channel only) | 76 acres | 7.6 acres | 84 acres | |

| # Mechanized placer leases | 2-large leases 8-small leases |

3- small leases | 13 leases | |

| Life of plan disturbance due to mechanized placer mining (uplands/floodplains) | 427 acres | 80 acres | 507 acres | |

| Total lease disturbance (20 years) | 503 acres | 88 acres | 591 acres | |

| Acres open to leasing | 64,000 acres | 11,000 acres 161 | 85,000 acres | 160,000 acres |

Anticipated Activity Associated with Exploration Licenses in the White Mountains Under Alternative D

| Activities under Reasonably Foreseeable Exploration and Development | High Potential Lands Lode REE | Medium Potential Lands – Placer Gold | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| # Placer exploration licenses | 4 | 4 | |

| Area licensed for placer (acres) | 20,000 | 20,000 | |

| Acres of disturbance due to placer exploration licenses | 20 | 20 | |

| # Lode exploration licenses | 1 | 1 | |

| Area licensed (acres) | 11,000 | 11,000 | |

| Acres of disturbance due to lode exploration licenses | 50 | 50 | |

| Total disturbance from exploration licenses (20 years) | 50 acres | 20 acres | 70 acres |

M.3.2 Affected Resources

M.3.2.1 Cultural and Paleontological Resources

Affected Environment

Placer gold prospecting and mining has occurred in some drainages in the White Mountains NRA for more than 100 years. The

specific areas outlined in Alternative D equate to areas of known historic mineral activity. Non-systematic archaeological

surveys in these areas have found historic mining sites immediately adjacent to portions of all creeks addressed in this alternative.

Similarly, Alaska Native prehistoric sites have been found along two of the creeks in this alternative, in spite of the almost

complete lack of archaeological surveys aimed towards finding such sites in the project area. There are almost certainly more

such sites.

Environmental Consequences

Section M.3.1 of this appendix describes the nature of the proposed hardrock mineral leasing. Alternative D outlines disturbance

of up to: 507 acres by mechanized placer mining operations, 70 acres from the issuance of exploration licenses, and 84 acres

by suction dredging in and alongside specified creeks (including Ophir, Bear, Trail, Quartz, Champion, and Little Champion

creeks).

Surface disturbing activities, including mining and exploration activities outlined here, directly and adversely impact cultural

and paleontological resources. Disturbance to prehistoric sites by any particular mining or exploration operation would need

to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Their locales on the landscape are a bit more predictable than are historic mining

sites. In sum, hardrock mineral leasing would likely directly and adversely impact all manner of surface and buried cultural

and paleontological resources.

Similarly, new access roads might be authorized to reach future valid mineral leases. New road construction has a direct and

adverse effect on cultural and paleontological resources. It also has an indirect effect when new users (such as recreators,

hunters, and those interested in procuring forest and woodland products) gain access to previously isolated lands. With more

resource users accessing BLM-managed lands, the potential increases for more people finding surface cultural resources and

adversely impacting them, whether intentional or not.

Cumulative Effects

Cumulative impacts to cultural and paleontological resources can occur through incremental degradation of the overall resource

base. Excepting especially rare or unique sites, the destruction of any one, two, three, or more sites would likely not impact

the overall, areal resource base, as there would probably be more of any similar type of site elsewhere in the planning area.

However, cultural and paleontological resources are a non-renewable resource and the loss of any one of them is one less from

a finite total. There would eventually be a point at which the cumulative overall destruction of sites would limit management

options within any defined area, such as the planning area. Hardrock mineral leasing in the White Mountains would contribute

to this cumulative effect.

Many low-level, seemingly minor impacts (such as walking or camping on a site) can slowly and cumulatively grow into a larger

direct adverse effect over time. Similarly, visitors to sites often feel an urge to connect with the past by removing a piece

of the site when they leave, like an artifact. Removal of a one, two, three, or more artifacts would not likely affect overall

site interpretation. However, the point would come when enough artifacts are removed, that the cumulative removal would irreversibly

affect any interpretations that can be made about that site. By promoting and increasing use and visitation upon public lands,

hardrock mineral leasing may inadvertently adversely impact cultural and paleontological sites in this cumulative manner.

M.3.2.2 Fish and Aquatic Species

Methods of Analysis

Indicators: For aquatic resources, fish, and Special Status Species, the indicators used to identify the level of impact include water

quality, riparian vegetation, streambank stability, and stream miles open to leasing of hardrock minerals.

Methods and Assumptions: Potential impacts on fish and aquatic resources are based on interdisciplinary team knowledge of the resources and the planning

area. Impacts were identified using best professional judgement and were assessed according to the following assumptions:

| • | Healthy riparian areas are critical for properly functioning aquatic ecosystems. Improvements or protection of riparian habitats would indirectly improve or protect aquatic habitats and fisheries. Adverse impacts to riparian habitats would indirectly degrade aquatic habitats and fisheries; |

| • | All of the anadromous streams or extent of anadromy within the area proposed for hardrock mineral leasing may not yet be identified; |

| • | A hardrock mineral leasing program would result in an increased number of placer mining operations with the potential to adversely affect fish and aquatic resources, including BLM Alaska watch list species and the outstandingly remarkable fisheries value for Beaver Creek; |

| • | All BLM land use authorizations would incorporate appropriate project design, Procedures, and mitigation to ensure no adverse long-term (greater than 20 years) impacts to water quality and aquatic habitats exist. |

| • | The BLM would identify channel reconstruction activities. Reconstructed stream channels would be designed by an individual(s) trained and qualified for the task and the channel would be built as designed. |

| • | Reclamation techniques would use an “adaptive management” approach to address potential problems allowing for corrective actions should they become necessary. These techniques would ensure applicable performance standards and required conditions are met at the conclusion of operations. |

| • | The timeframes associated with long- and short-term impacts assume that channel equilibrium is maintained. |

Affected Environment

A general description of fish and fish habitat within the planning area, including areas specific to Alternative D, is in

section 3.2.4.1 of the Eastern Interior Draft RMP/EIS (BLM 2012a) and is incorporated by reference. The planning area supports

17 native fish species. None of these species are listed as threatened or endangered. With few exceptions, the current condition

of fish species is good, and most fish populations are self-sustaining.

Approximately 160,000 acres are recommended open to hardrock mineral leasing in Alternative D, including 250 miles of headwater

streams located in the southeast portion of the White Mountains NRA. These streams form the headwaters of Beaver Creek WSR

(Figure M.1). These headwater streams are clear, rapid streams with long riffles, few pools, with an average width of 50 feet

(Rhine 2005). The substrate generally consists of a gravel-cobble mixture (3 to 12 inches in diameter). Although some placer

mining activity has occurred in headwater areas of Beaver Creek, most of these streams are thought to be in pristine condition,

with the exception of Nome Creek. Nome Creek was heavily placer mined for gold from the early 1900s to the late 1980s. Mining

disturbed more than seven miles of stream and by the 1980s the floodplain was largely obliterated (Kostohrys 2007). From 1991

to the present, the BLM has been working to restore the floodplain, reestablish riparian vegetation, and maintain a single

thread channel. The BLM has expended an estimated $450,000 on the Nome Creek reclamation project (USKH 2006).

Fish species found within the upper Beaver Creek watershed that are adjacent to or within areas recommended open to mining

include Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), Arctic grayling (Thymallus arcticus), whitefish (Coregoninae spp.), and slimy sculpin (Cottus cognatus). Beaver Creek also supports regionally significant fish species which include small populations of coho (O. kisutch), and summer chum salmon (O. keta). The creek also supports moderate to high densities of Arctic grayling and northern pike (Esox lucius) which provide important recreational fishing opportunities. These populations of regionally significant fish species, unique

concentrations of Arctic grayling, and the river’s pristine habitat support BLM’s identification of fish as an Outstanding

Remarkable Value (ORV) for Beaver Creek (BLM 2012a, Appendix E).

The BLM monitored Beaver Creek Chinook salmon escapement from 1996 to 2000 and the data revealed a declining trend similar

to the overall decline of Yukon River Chinook salmon (Volk et al. 2009). The Beaver Creek Chinook salmon escapement for these

years ranged from 114 to 315 Chinook salmon. Although Beaver Creek Chinook salmon were designated as a BLM Alaska sensitive

species in 2004 due to the downward trend of this small population, they were recently removed from that list and placed on

a watch list. Since 2000, the Alaska Department of Fish & Game (ADF&G) has considered the Yukon River Chinook salmon stock

as a stock of yield concern based on escapement performance, expected yields, and harvestable surpluses (Howard et. al. 2009). Beaver Creek Chinook are

a component of the Yukon stock. Between 1996 and 2000, the overall Yukon River Chinook escapement range from the highest (about

300,000) to the lowest (about 100,000) dating back to 1982. Beaver Creek contributes a small percentage of the overall Yukon

River Chinook salmon stock. The Yukon stock, however, is made up of numerous genetic stocks (such as the Beaver Creek stock)

all of which are considered important to the overall health and viability of the stock.

The ADF&G Anadromous Water Catalog identifies Chinook salmon spawning and rearing in Beaver and Ophir creeks and Chinook

spawning in Nome Creek (Figure M.2). Adult Chinook salmon in spawning condition have been observed at the confluence of Bear

and Champion Creek (E. Yeager, pers. comm. May 15, 2012). That location is many miles farther upstream than what the Anadromous

Waters Catalog identifies as the extent of anadromy. This reinforces ADF&G’s assumption that approximately 50 percent of the

anadromous streams or extent of anadromy have not yet been identified.

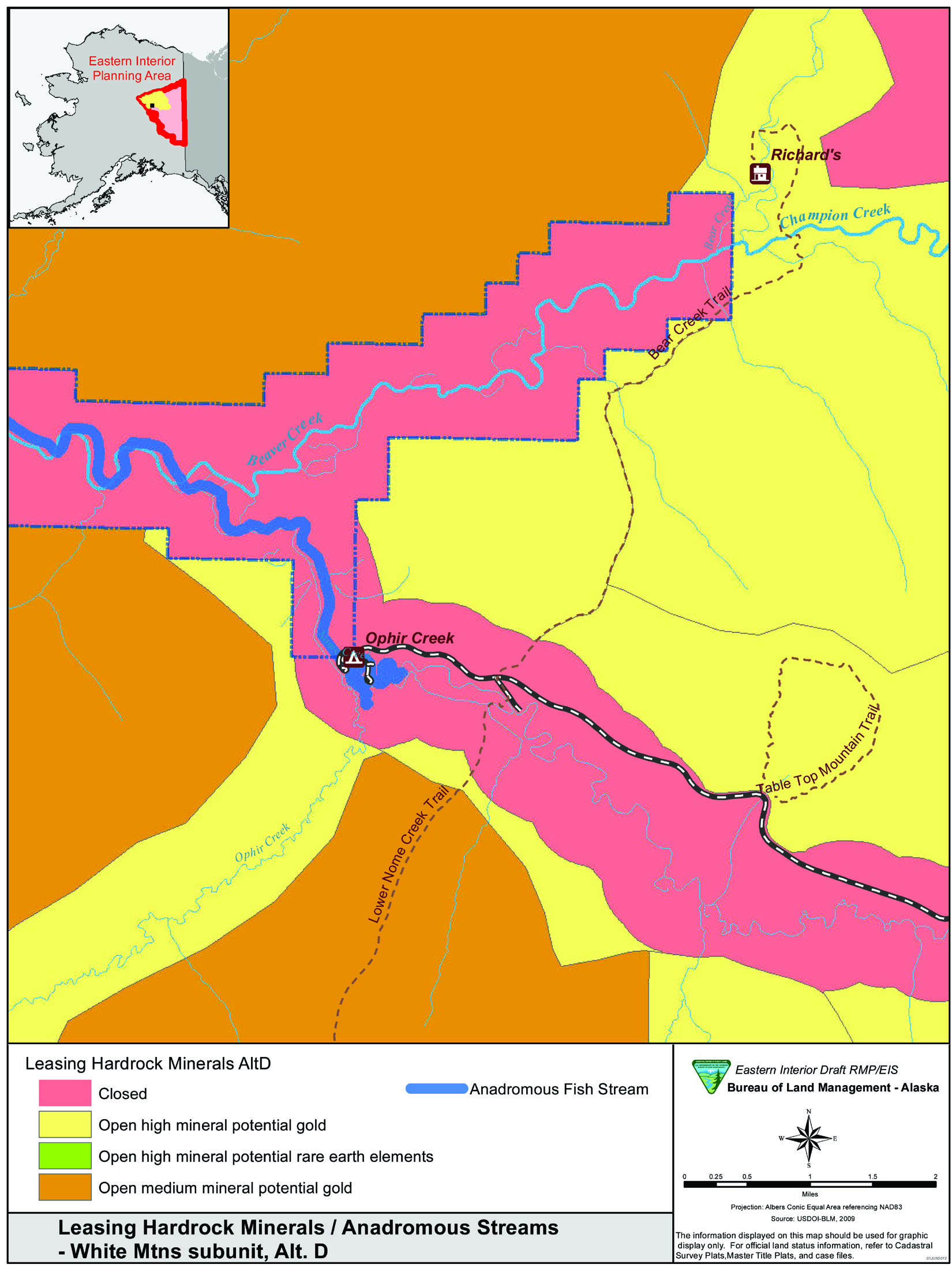

Map of Anadromous Streams in Headwaters of Beaver Creek

The excellent opportunity for Arctic grayling fishing was one of the values identified for establishing Beaver Creek as a

component of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System (BLM 1983). In 2000, the BLM and ADF&G performed an Arctic grayling

study on the upper 30 miles of Beaver Creek, including the area between the confluence of Bear and Champion creeks and the

confluence of Nome Creek (Fleming et al. 2001). This study estimated the population density of Arctic grayling at 1,325 per

mile, which is higher than other studies on summer feeding populations in Alaska by as much as 44 percent. The study also

revealed an increase in the size of grayling as the study moved upstream to the headwaters of Beaver Creek. This pattern was

reinforced by other studies that found large male Arctic grayling migrating from downstream areas to Bear and Champion creeks

during late May and June, while females and smaller males move into these areas during July and August (Rhine 1985). Within

the upper 100 miles of Beaver Creek, the headwater streams (e.g., Bear and Champion creeks) have produced the largest and

oldest Arctic grayling based on BLM and ADF&G fish sampling efforts and reports from recreational anglers (T. Dupont, pers.

comm., May 22, 2012). This pattern reflects the generally accepted life-history paradigm for Arctic grayling that larger and

older fish spend the summer feeding period in headwater areas and tributaries of rapid runoff rivers in Alaska (Armstrong

1982). Although Arctic grayling primarily use the headwater streams for summer feeding, some evidence of spawning has been

observed (Rhine 1985; Kretsinger 1986) and may justify future inventory work.

Environmental Consequences

The effects on fish and aquatic habitats of mining (and exploration) for hardrock minerals in the White Mountains Subunit

under mineral leases would be similar to those described for locatable mineral development in other parts of the planning

area. These effects are described in section 4.3.1.4 of the Eastern Interior Draft RMP/EIS (BLM 2012a) and are incorporated

by reference.

Suction dredging, a type of placer mining, can have both beneficial and adverse effects on fish and aquatic habitat depending

on the timing and location of the activity.

Suction dredging has been shown to locally reduce benthic (bottom dwelling) invertebrates (Thomas 1985; Harvey 1986), cause

mortality to early life stages of fish due to entrainment by the dredging equipment (Griffith and Andrews 1981), destabilize

spawning and incubation habitat, remove large roughness elements such as boulders and woody debris that are important for

forming pool habitat and that can govern the location and deposition of spawning gravels (Harvey and Lisle 1998), increase

suspended sediment, decrease the feeding efficiency of sight-feeding fish (Barrett et al. 1992), and reduce living space by

depositing fine sediment (Harvey 1986).

Conversely, suction dredging may temporarily improve fish habitat by creating deep pools or by creating more living space

by stacking large non-embedded substrate (Harvey and Lisle 1998; Figure M.2). In dredged areas, invertebrates and periphyton

are known to recolonize relatively rapidly, as long as the disturbance area is sufficiently limited to maintain populations

of recolonizing organisms (Griffith and Andrews 1981; Thomas 1985; Harvey 1986). In addition, dredge tailings may increase

spawning sites in streams lacking spawning gravel or streams that are armored by substrate too large to be moved by fish (Kondolf

et al. 1991). In some cases, reduced visibility caused by elevated levels of turbidity can diminish the feeding efficiency

of fish, while at the same time the reduced visibility may lessen the risk of predation (Gregory 1993).

Suction dredging operations within the Steese Subunit have been known to adversely impact streambank stability as well as

riparian and stream channel function. Although disturbance to streambank and riparian habitats and alterations to the stream

course is prohibited for suction dredging operations, in some cases these areas have been impacted. This type of activity

results in an overwidened and shallow stream course, which is braided around stacked piles of large substrate. These impacts

adversely affect riparian and stream function and if not reclaimed may persist for extended periods of time (years/decades)

due to the amount of stream energy required to redistribute this large-sized substrate in the stream channel. It is assumed

that these situations would be limited and that lease and license stipulations would minimize the level and duration of impacts

to aquatic resources.

The anticipated number of suction dredging operations during the life of this plan is 11 (Table M.3). There would be 250 miles of stream open mineral leasing with an anticipated disturbance of 84 acres, or 14 miles of stream.

Suction dredging operations are anticipated to disturb 22,000 cubic yards of stream gravel over the life of this plan or the

equivalent of 2,200 typical (10 cubic yard) dump truck loads of stream gravel. Impacts from suction dredging operations that

do not alter streambank stability or adversely impact riparian and stream channel function, and adhere to stipulations in

the suction dredge permit, are likely to be minimal and of short-term duration (less than or equal to five years).

Mechanized Placer Leases – Conventional Mining

For Alternative D, fish and aquatic resources would be primarily affected by surface-disturbing activities which alter stream

channels and floodplain connectivity, remove or impair riparian vegetation and function, or result in soil erosion and sedimentation

to fish and aquatic habitat. These activities would include mechanized placer mining and associated road construction that

occur within or adjacent to riparian areas or waterbodies.

Conventional mechanized placer mining involves the use of heavy equipment to access gold deposits. One method of mine development

is to move the stream into a bypass channel, while the original stream channel is excavated for gold deposits. During this

process the streambed, streambanks, and riparian vegetation are physically removed in order to access gold-bearing fluvial

deposits which may extend to the bedrock. This method destroys the existing fish and aquatic habitat and eliminates all biological

stream functions. Impacts to fish and aquatic resources can be severe and last for decades under the stream-altering bypass

method (Tidwell et al. 2000, Arnett 2005, Viereck et al. 1993; Milner and Piorkowski 2004; BLM 1988 a, b, and c). Soil erosion

from large surface disturbing activities (such as mechanized mining) often results in poor water quality and elevated turbidity

levels harmful to fish and fish habitat far beyond the impact site. The River Management Plan for Beaver Creek National Wild

River (BLM 1983c) stated that placer mining activities in the headwaters of Beaver Creek resulted in turbid water conditions

as far as 30 miles downstream. Surface management regulations have since changed, in part to reduce adverse impacts to water

quality from mining. The severity and duration of impacts are substantially reduced when mining operations occur outside of

the stream channel and active floodplain.

The anticipated number of mechanized placer mining leases during the 20-year life of this plan is 13 (BLM 2012b). Approximately

250 miles of stream would be open to leasing for mechanized placer mining with an anticipated amount of disturbance of 507

acres. This disturbance would likely occur within floodplain areas and/or in the stream channel. In an attempt to quantify

the number of stream miles that may be directly impacted by leasing, the length of a typical mining claim block (660 feet)

from other subunits was used. The anticipated number of stream miles directly impacted by leasing would be eight miles. The

likelihood of impacts would be greatest in the high development potential areas, which, contain more than half of the stream

miles open to mechanized leasing.

If mining did occur, the ROPs specific to fish and aquatic species (Appendix A) would improve the likelihood of obtaining

desired future conditions for aquatic habitats within an accelerated timeframe after reclamation. A range of success would

be expected based on several factors. These factors include baseline data collection, stream channel design/construction technique,

the reclamation measures specified for the particular operation, the watershed characteristics, the capability of the site

to revegetate, and the probability of experiencing a flood event prior to the reestablishment of riparian vegetation that

is capable of dissipating stream energy and preventing erosion.

Assuming that baseline data is collected, reclamation is designed using the best available techniques such as those outlined

in the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s (NRCS, 2007) Stream Restoration Design, National Engineering Handbook, Part 654, and all of the factors previously mentioned are favorable, it is likely that instream habitats would rehabilitate within

five years following reclamation. In these cases, impacts would be expected to be minor and short-term. However, stream channel

design/reconstruction and aquatic habitat rehabilitation is very complex, especially within the planning area due to the harsh

environmental conditions (such as short growing season, aufeis) and limited availability of hydrography data. Recognizing

this complexity, a more realistic outcome may be a strong positive trend toward the desired habitat conditions within five

to ten years under this management scenario. It would be essential that reclamation plans incorporate stream channel design

based on channel forming discharge (typically a 1.5 year recurrence interval) and the floodplain be capable of transporting

100-year flood flows. This would minimize the chance of reclamation failure and the need for subsequent reclamation work by

the operator.

In summary, placer mining can negatively affect fish and aquatic resources by degrading or eliminating aquatic habitat; reducing

available food sources and water quality; reducing available pool habitat; eliminating riparian vegetation and function; creating

sparsely vegetated valleys and floodplains with slow rates of natural revegetation and unstable stream channels with highly

erodable beds and banks; altering the longitudinal slope, geometry, and sediment transport rates in streams; and, creating

undersized or absent floodplains.

Mineral Exploration Licenses

It is anticipated that there would be four placer exploration licenses and one lode exploration license. Placer exploration

licenses may encompass 20,000 acres with an anticipated disturbance and reclamation of 20 acres over the 20-year life of this

plan. The impacts to fish and aquatic resources would vary depending on the location, type of exploration activities, and

subsequent reclamation, all of which would be analyzed during a site-specific NEPA analysis prior to approval of exploration

licenses and exploration plans.

Potential adverse impacts would likely be from surface erosion of disturbed soils and the destruction of riparian vegetation

resulting in elevated turbidity levels and sedimentation to nearby water bodies. The effects of excess sediment and the removal

of riparian vegetation to fish and aquatic resources is described in section 4.3.1.4.1 of the Eastern Interior Draft RMP/EIS,

which is incorporated by reference. Although sediment is a natural part of the aquatic ecosystem, an increase in fine sediment

has the potential to affect the availability of food, predator avoidance, immune system heath, and reproduction of fish and

aquatic species. The ROPs (Appendix A) should reduce impacts from exploration to a negligible level with short duration given

the anticipated level of disturbance from exploration activities. The larger the surface disturbance and the closer it is

to the stream, the greater the severity and duration of the impact.

It is anticipated that one lode exploration license would be requested in the Roy Creek REE deposit, resulting in 50 acres

of disturbance. While it is unlikely that fish or fish habitat studies have ever been performed in the headwaters of Roy Creek,

it is reasonable to conclude that fish may not be present in the headwaters of this relatively small, high gradient stream.

Direct impacts from lode exploration are not anticipated. Potential indirect adverse impacts from surface erosion would be

similar to those described above for placer exploration activities.

Previous surveys in the Roy Creek area indicate that the soils are mainly of the granitic type (John Hoppe, pers. comm. May

10, 2012) that pose little threat to fish and aquatic life when disturbed and exposed to air and water. Although unlikely,

if soils containing sulfide bearing ore were disturbed and exposed to air and water during exploration activities, acid mine

drainage may occur and result in adverse indirect impacts to downstream waters. Acid mine drainage can cause physical, chemical,

and biological degradation to aquatic habitat (Jennings et al. 2008). Predicting the risk of acid mine drainage at mine sites

is often inaccurate (Jennings et al. 2008). It will be necessary to collect site-specific information variables and data to

predict the potential for acid mine drainage in the Roy Creek area.

Outstandingly Remarkable Values and Watch List Species

As noted previously, the Arctic grayling fishery was one of the values identified when Beaver Creek was established as a component

of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System (BLM 1983c). Fish are currently proposed as an outstandingly remarkable value

for Beaver Creek (BLM 2012a, Appendix E). As such, fish habitat within Beaver Creek and its tributaries in the White Mountains

NRA have been managed to maintain and/or enhance fish populations with an emphasis on Arctic grayling (BLM 1986). Similarly,

a major goal for the NRA is to protect and maintain the water quality of Beaver Creek to meet state water quality standards

and promote a quality fishing experience (BLM 1986b). Mechanized placer mining within the floodplain and/or stream channels

of Beaver Creek’s principal tributaries would not maintain or enhance fish habitat and populations or water quality. The White

Mountains NRA Record of Decision and Resource Management Plan (BLM 1986b) states that “Extensive placer mining on Beaver Creek

or its principal tributaries would be in conflict with recreational purposes because of degradation to natural and primitive

values of the Beaver Creek WSR corridor and damage to Arctic grayling habitat”. It also states that sport fishing on Beaver

Creek contributes to public enjoyment of the NRA and fish habitat in tributary streams should be protected because they contribute

to fish populations in Beaver Creek.

Beaver Creek Chinook salmon are currently a BLM Watch List species (BLM 2010). This species should be emphasized for additional

inventory, monitoring, or research efforts to better understand the population or habitat trends. Beaver Creek Chinook salmon

are a component of the Yukon River Chinook stock, a stock of yield concern since 2000 (Howard et al. 2009). Beaver Creek Chinook salmon spawn and rear immediately downstream and potentially within

the area proposed for opening to conventional mining (Figure M.1). The adverse impacts from mechanized mining, including the

downstream effects and habitat degradation, could cause the Beaver Creek Chinook to become designated as a BLM Alaska Sensitive

Species.

Cumulative Effects

Cumulative impacts to fish and aquatic resources consist of past, present, and reasonably foreseeable future impacts, including

impacts on non BLM-managed lands. Hardrock mineral leasing in Alternative D would add to cumulative impacts from exploration

and development of locatable and leasable minerals elsewhere in planning area, including on state and private lands.

Fish and aquatic resources have been adversely impacted from past mechanized mining activity in the Beaver Creek drainage.

The majority of these impacts occurred from 1900 until the mid-1980s in Nome Creek, where extensive mining for placer gold

obliterated seven miles of stream and floodplain (Kostorhys 2007). This activity resulted in the direct loss of fish habitat

and sediment pollution to Beaver Creek. Although habitat conditions in Nome Creek have greatly improved from nearly 20 years

of reclamation work by the BLM, desired conditions for aquatic habitat have not yet been achieved (desired future conditions

are described in section 2.4.1.3 of the Draft RMP/EIS, BLM 2012a). Portions of Nome Creek have not been reclaimed and are

not likely to be in desired condition for aquatic habitats. Mechanized mining activities have also occurred in other tributaries,

but to a much lesser extent. There are no known current mining activities in the Beaver Creek drainage.

A hardrock mineral leasing program would open 160,000 acres to the leasing and exploration of formally locatable minerals

in the White Mountains NRA with an anticipated disturbance of 661 acres and eight miles of stream. Suction dredging activities

may impact 14 miles of stream. Past and future mechanized mining proposed in this alternative may result in approximately

20 miles of stream within the NRA that would not meet the desired conditions for aquatic habitats. Cumulative impacts specific

to the NRA would be in addition to the cumulative impacts described in section 4.3.1.4.2. of the Eastern Interior Draft RMP/EIS

(BLM 2012a). Cumulative impacts from Alternative D, would have the greatest potential for adverse impacts to fish and aquatic

resources relative to the other alternatives.

M.3.2.3 Non-Native Invasive Species

Alternative D also allows the most latitude to OHV use and rights-of-way and would result in the greatest disturbance to soil

and vegetation in the areas recommended open to hardrock mineral leasing. This would create the greatest potential for the

introduction of nonnative invasive plant species (invasive plants) within the White Mountains NRA. Equipment imported for

mineral exploration and development activities often harbor seeds of invasive species that could dislodge and germinate at

these remote sites.

The reasonable foreseeable development scenario (RFD) forms the basis for evaluating the impacts to resources (section M.3.1)

from hardrock mineral leasing. The total disturbance over the life of the plan is expected to be 661 acres from all hardrock

leasing and exploration licenses, a relatively small portion of the 160,000 acres open to exploration and development. Assuming

that exploration and development occurs throughout the open area, invasive plant species could be introduced in a dispersed

rather than concentrated pattern, complicating control and containment.

The RFD includes the assumption that 20 miles of roads would be built in support of new placer developments. The roads are

linear vectors for the introduction and spread of invasive plants into these remote areas. Seeds from infestations along roads

can move along other intersecting linear features, such as trails and waterways, further spreading undesirable nonnative species

into remote areas. For example, infestations of white sweetclover (Meliotus officianalis) have been documented on sand bars along the Nenana River, spreading from source populations upstream (Conn et al. 2008).

Section 4.7.1.3.4 of the Eastern Interior Draft RMP/EIS (BLM 2012a), which is incorporated by reference, contains analysis

of rights-of way development in the White Mountains NRA for Alternative C. Impacts identified in this section apply to the

roads in support of new placer developments analyzed in this supplement.

Any natural or human-caused disturbance to the landscape provides an opportunity for invasive plants to become established.

Equipment, watercraft, vehicles, and gear may harbor seeds that may then be transported to project sites. Climate change may

accelerate the ability for invasive plants to become established (Rupp and Springsteen 2009). More general information about

vectors and impacts from introduction and spread of nonnative invasive plants are in Chapter 4 of the Eastern Interior Draft

RMP/EIS (BLM 2012a). This information is incorporated by reference. Section 4.3.1.5 discusses effects common to all subunits.

Section 4.7.1.3 of the Draft RMP/EIS contains analysis of impacts for locatable minerals on 4,000 acres of valid existing

rights outside the NRA and other decisions, but assumes no hardrock leasing within the White Mountains NRA. Impacts from hardrock

mineral leasing would be similar to those from locatable mineral exploration and development.

ROPs and Leasing Stipulations in Appendix A of the draft RMP/EIS and those modified in this supplement (shown in Appendix

A of this document) to mitigate impacts from hardrock mineral leasing would be applied on a case-by-case basis to leases and

exploration licenses. ROPs in section M.4.2.10 of this document specifically address eliminating or minimizing the introduction

and spread of invasive plants by prescribing standards for vegetation treatment, revegetation with native plants, reclamation

for roads and trails, and salvage of vegetative mat and topsoil. Other ROPs in Appendix A would also help limit the introduction

and spread of invasive plants.

Nonnative invasive species other than plants may be introduced by exploration or development when equipment from Canada or

other parts of the United States are imported to the work sites. This equipment can harbor insect eggs, larvae, pupae, adult

or other viable life cycle stages and other undesirable pathogens and pests. Little documentation exists that invasive species

other than plants have been introduced into Interior Alaska. Over the life of the plan where there may be concerns about other

invasive species, however, permit stipulations to mitigate introduction of insects, other pests and pathogens would be developed

on a case-by-case basis.

Indirect impacts would result where invasive plants become established due to hardrock exploration development, including

potentially long-term changes in plant community structure and diversity and wildlife habitat degradation. Costs include long-term

monitoring and control. Containment and control of invasive plants for the long-term may also include further soil disturbance

and the application of herbicides.

Cumulative Effects

Cumulative effects of past, present and reasonably foreseeable actions that are common to all for nonnative invasive species

have been developed in section 4.3.1.5.2 of the Eastern Interior Draft RMP/EIS (BLM 2012a). Cumulative effects specific to

the White Mountains Subunit for nonnative invasive species are in section 4.7.1.3.6. The combination of the removal of vegetation

for exploration and development, increased disturbance of riparian vegetation and bank stability from multiple stream crossings,

user-created trails, new support roads in the southeast portion of the White Mountains NRA, and present and potential future

actions on adjacent federal, state and private lands increases the footprint for invasive plants to become established and

spread from adjacent development into the relatively weed-free NRA. Ongoing climate change is expected to result in an increase

in the number of nonnative species that can become established in subarctic areas due to longer frost-free season and thawing

of permafrost. Changes in precipitation projected for the Eastern Interior may also benefit invasion by invasive plants that

outcompete native plants and alter wildlife habitat.

M.3.2.4 Soil and Water Resources

Compared to other alternatives, Alternative D would result in the greatest disturbance to soil resources and adverse impacts

to water quality because selected areas (Figure M.1) would be open to hardrock mineral leasing. Ongoing climate change would

also affect these resources and may increase the magnitude of effects from mining.

Anticipated disturbance in the White Mountains NRA is estimated at 507 acres by mechanized placer mining operations, 20 acres

associated with the issuance of placer exploration licenses, 50 acres from the issuance of rare earth element exploration

licenses, and 84 acres of disturbance from placer gold suction dredging in areas with high placer gold potential, including

Ophir, Bear, Quartz, Champion, Little Champion and Moose creeks. Mining activities would be limited to approximately 160,000

acres in areas of known historic mineral activity in the south/southeast part of the White Mountains NRA. Lands within one-half

mile of Nome Creek would be closed to leasing because of long-term ongoing stream reclamation as well as parcels of wetland

acreage committed in perpetuity as U.S. Army Corps of Engineers compensatory wetland mitigation acreage.

Disturbance to soil and water resources by any particular mining or exploration operation would need to be assessed on a case-by-case

basis. Impacts to soil and water resources vary depending on the development methods used, size of the operation, and number

of mines. Because 160,000 acres would be open to mineral development under Alternative D there would be increased potential

for adverse impacts to soil and water resources. Impacts would be reduced through application of ROPs and site-specific analysis

of subsequent authorizations.

Effects from Mechanized Placer

Probable impacts to soil and water resources from placer mining were described in detail in the Beaver Creek Placer Mining

Final Cumulative EIS (BLM 1988b). Impacts can vary considerably depending on factors including site characteristics, size

of the disturbed area, and mining methods. Where placer mining operations utilize heavy equipment, the following impacts could

be expected.

Placer mining can have an adverse effect on the existing soil profile structure by stripping of overburden and riparian/wetland

vegetation. The usual procedure is for the overburden (including organic materials) to be stripped, coarse underlying materials

separated from gold-bearing material in the processing plant, and fine materials discharged to a series of settling ponds

with recycled water used by the processing plant. There is an irretrievable loss of any soil that enters waterways and is

transported downstream.

Erosion of soils from non-point sources typically contribute to the sediment load of stream systems and may result from stream

crossings, roadways directly adjacent to stream channels, improved roads and trails which converge down-gradient to stream

channels.

The primary impact to water quality from mining is an increase in sedimentation and turbidity. Some direct effects on water

quality can be anticipated during the development stage of an operation due to the construction of settling ponds and stream

bypasses, and through re-channelization of the stream. This would result in short-term increases in sediment levels and turbidity

while equipment operates near or in the active stream channel.

Leasees would be required to meet Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation water quality standards and acceptable discharge

standards available online at http:\\dec.alaska.gov/commish/regulations/index.htm. It is anticipated that turbidity as a result

of direct and indirect discharge from placer mine operations would meet ADEC water quality standards. However, it is likely

that occasional high water or failure of water control structures would introduce sediments collected by the water treatment

system into the stream channel. This would result in short-term increases in turbidity and sediment load levels and possible

localized sedimentation of the stream substrate. The degree of impact would depend on the amount of material released and

the streamflow at the time of release.

Stream channel morphology would be directly affected in all areas where activities associated with mining occur in the active

channel; by-pass channels are usually constructed to allow mining in the active channel.

Indirect impacts to water quality would occur through non-point source erosion from disturbed areas associated with placer

operations including access road and trails and equipment staging areas directly adjacent to stream channels. Channel readjustment

would occur where the active channel was modified. These processes increase suspended sediment into the stream system, particularly

during spring break-up and floods.

The impacts to soil and water resources could be expected to decrease after cessation of mining, successful revegetation of

the disturbed areas, and stabilization of the disturbed channel. It is estimated that reestablishing vegetation on placer

waste rock piles may take decades. The rate of succession (revegetation) seems to be heavily influenced by the proportions

of particles of silt and clay size in the surface layer of the tailings (Rutherford and Meyer 1981).

ROPs (Appendix A) have been developed to reduce impacts to soil and water resources that may result from hardrock mineral

leasing activities. Additional mitigation measures, if necessary, could be developed during NEPA analysis of specific mineral

leases or exploration licenses. Water quality monitoring requirements (Wagner et al. 2006) would be defined through this process.

Daily stream flow and water quality is currently monitored on lower Nome Creek and on Beaver Creek near its confluence with

Victoria Creek to document daily, annual, and long-term variation in flows and water quality. The BLM would continue to monitor

water quality and in-stream flow in selected streams and lakes to ensure that state water quality standards were met and to

document changes in stream flow. Activities expected to adversely alter natural flows would not be permitted.

Effects from Suction Dredging

Suction dredge mining activities have the potential to affect soil and water resources, particularly if operations require

access over steep terrain or permafrost soils where surface disturbance may result in increased erosion. Adverse impacts could

result from equipment transport and storage, fuel spills, unauthorized expansion of existing trail networks, as well as from

compaction of soils at long-term camping sites associated with suction dredge mining operations.

In Interior Alaska a majority of the suction dredge operations occur in the Fortymile River area. The USGS conducted a systematic

water quality study of the Fortymile River and many of its major tributaries in June of 1997 and 1998 (Wanty et al. 1999).

Surface-water samples were collected for chemical analyses to establish regional baseline geochemistry values and to evaluate

the possible environmental effects of suction-dredge placer gold mining and bulldozer-operated placer gold mining (commonly

referred to as cat-mining). They concluded, based on water-quality chemistry and turbidity data, that the suction dredges

had no apparent impact on the Fortymile River system, although possible effects on biota were not evaluated. One of the three

cat-mining operations monitored, however, had adverse impacts on local water quality and streambed morphology.

Cumulative Effects

Cumulative impacts to soil and water resources consist of past and current impacts in addition to reasonably foreseeable future

impacts, regardless of whether these impacts were from private, state, or federal actions. Any proposed resource development

involving surface disturbance has the potential to cumulatively impact soil and water resources. Incremental cumulative degradation

of soils and water resources within a watershed can occur, for example, through mining operations on selected stream segments.

For each individual mining operation a small direct loss of soil and some small degradation of water quality are likely. As

the number of mining operations increase in a given watershed the cumulative soil loss and cumulative impact to water quality

can have long-term adverse impacts on soil stability, riparian habitat, fisheries habitat and water quality.

Cumulative impacts can also result from repetitive use of an area, such as a single OHV stream crossing along a user-created

trail. Minor disturbance may result from a single crossing, however, multiple use of an unimproved OHV stream crossing site

can result in substantial cumulative impacts including soil compaction, damage to riparian vegetation, erosion along user-created

trails and potential decrease in bank stability and local water quality.

Placer mine development has occurred in the Steese-White Mountains area since the early 1800s using a variety of mechanized

methods including dredges, draglines, dozers, and excavators. The soil profile is typically destroyed for long periods in

areas of active dredging or sluicing, with shorter-term impacts of soil compaction and alteration in areas of facilities,

roads, and trails. Water quality is often degraded by increased siltation depending on site characteristic and the type of

mining operation.

The total disturbed area from historic placer activity on BLM-managed lands in the planning area is estimated at 7,500 acres,

with less than 500 acres likely disturbed by past mining activity in the White Mountains. Alternative D of the Draft RMP/EIS

would recommend opening selected areas to mining, potentially resulting in development of new access roads and mine operations.

A portion of this projected mining, however, would likely occur in previously mined areas. Development of an estimated 61

small-scale (20 to 30 acres) placer mines and eight large-scale (60 to 80 acres) would be expected on BLM-managed land under

Alternative D, all outside of the White Mountains NRA. The addition of a hardrock mineral leasing program in the White Mountains

NRA would potentially add two large-scale placer mines, 11 small-scale placer mines, and 11 suction dredging operations in

the White Mountains. This level of activity is projected to add an additional 661 acres of new disturbance in the NRA.

In its 2007 Mineral Industry Report, the Alaska Division of Geologic and Geophysical Surveys (DGGS), lists 81 separate companies

or individuals that were estimated to be producing gold in the planning area (Szumigala et al. 2008). The amount of acreage

on state and private land that has been disturbed or reclaimed by mining operations within the planning area is uncertain.

Two large-scale lode mines, Pogo and Fort Knox, are in operation on state lands within the planning area. One potential lode

mine, “Money Knob”, is located near the town of Livengood along the western boundary of the White Mountains subunit. If potential

lode mines are developed, varied impacts to soil and water resources would be expected depending on the type of mine development

and ore processing methods.

M.3.2.5 Special Status Species

Wetland, riparian, and aquatic habitats support most of the BLM Alaska sensitive animal species. Olive-sided flycatcher, blackpoll

warbler, rusty blackbird, Alaskan brook lamprey, Alaska endemic mayfly (Rithrogena ingalik), a mayfly (Acentrella feropagus), and a stonefly (Alaska sallfly, Alaskaperla ovibovis) are BLM Alaska sensitive species that are dependent on these habitats and may occur in the hardrock leasing area, or downstream

in areas potentially affected by hardrock leasing activities. The Alaska tiny shrew (Sorex yukonicus) may also occur more frequently in riparian habitats. Placer mining and associated changes in access could result in substantial

localized impacts to riparian and aquatic habitats and species, if the species occurs in or downstream of the area of disturbance.

Rangewide impacts are unlikely to be substantial. Reclamation requirements for riparian and aquatic habitats should increase

reclamation success and reduce impacts for sensitive species occurring in these habitat types.

Olive-sided flycatcher, blackpoll warbler, and rusty blackbird are found in the White Mountains in low densities. These species

are widely distributed in the planning area. All are associated to some extent with riparian or wetland habitats. ROPs that

minimize impacts to riparian and wetland habitats through reclamation would reduce impacts over the long-term. Occurrence

of these species in other habitats and areas is dispersed enough that anticipated activities are unlikely to impact any of

them at a population level.

Alaskan brook lamprey is found in the Chatanika River, near the Elliott Highway bridge close to the Beaver Creek drainage

in the White Mountains NRA, but is not known to occur on BLM-managed lands. Alaska endemic mayfly, a mayfly, and Alaska sallfly

are not currently known to occur in the Beaver Creek headwaters or the White Mountains NRA, but data on distribution is extremely

limited. It is not known how much of these species habitat, if any, is encompassed by the hardrock mineral leasing area, but

disturbance of up to 591 acres of riparian habitats within the headwaters of Beaver Creek is not expected to result in impacts

at the population level nor cause a trend toward federal listing for any of these species.

The Alaska tiny shrew occurs in low density within a variety of habitats, but is most common in riparian shrub habitats. It

has been documented to occur in the Steese National Conservation Area near Twelvemile Summit. Widespread activities that clear

large areas of vegetation could negatively impact this species. Mining could have localized effects to shrew habitat, but

given the variety of habitats used and the low level of disturbance anticipated, would not likely occur at a scale or degree

to cause a trend toward federal listing.

Most BLM Alaska sensitive plant species occur in habitats with specialized conditions, such as: steep south-facing dry bluff

habitats; moist alpine herbaceous sites; rocky ridges, slopes, and screes; and, calcarious rocks or soils. Four species are

known to occur in the White Mountains: Douglasia arctica is known from Mount Schwatka, Victoria Mountain and VABM Fossil (Parker et al. 2003); Poa porsildii found in the Lime Peak and VABM Fossil areas; Ranunculus camissonis collected in the Lime Peak area; and, Trisetum sibiricum collected from below Mount Schwatka and on Lime Peak. Although not documented, there is a potential for BLM Alaska sensitive

plant species to occur in the mineral leasing area, particularly on the ridge between Quartz, Bear, and Champion creeks and

in the Roy Creek REE deposit. There is less potential for these species to occur in creek bottom habitats where placer mining

would occur. Given the habitat preferences for these species, the highest potential for impacts would be from REE mineral

exploration activities. Exploration activities would result in minimal surface disturbance and impacts would be localized

at drilling or trenching sites. ROPs SS-2 and SS-3 which require site-specific measures, such as avoidance, to protect sensitive

plant species populations or individuals would further reduce the potential for direct impacts.

Hardrock leasing would impact individuals of some BLM Alaska sensitive species, the distribution of which are generally not

well-known. Hardrock mineral leasing in the White Mountains NRA would result in greater impacts to sensitive species relative

to Alternatives A, B, and C, and would add to cumulative impacts described for Alternative D in section 4.3.1.7.2 of the Eastern

Interior Draft RMP/EIS (BLM 2012a). It is not anticipated, however, that the hardrock mineral leasing in Alternative D would

trend any sensitive species toward federal listing.

M.3.2.6 Vegetation

A direct loss of native vegetation on 661 acres (less than one percent of the area open to mining) is estimated to occur at

exploration and leasing operations during the life of the plan. Most of this vegetation would be riparian and wetland habitats.

Some of this area would be needed for ongoing operations and would remain unvegetated for several to many years. A portion

would be allowed to revegetate beginning within a year or two of disturbance. Times to reestablish vegetative cover would

vary widely. Areas which have adequate fine and organic soil materials and viable seed and vegetative plant parts revegetate

relatively quickly. Lease stipulations which require vegetation cover to meet pre-determined standards would result in faster

revegetation. Riparian areas in which the stream channel was disturbed and a stable stream channel was not established would

remain largely unvegetated until the channel stabilizes. Loss of fines and organic material through flooding and shifting

channels can delay revegetation for decades.

The roads and trails developed for access to exploration and mine sites would disturb an undetermined area of native vegetation

and supporting soils. Heavy, season-long use may result in significant loss of vegetation and degrading of soils in a variety

of vegetation types. Vehicles larger than 1,000 pound curb weight and 50 inch width would be allowed in some instances, resulting

in relatively greater impacts. Additional disturbance would occur through expansion of this network of roads and trails by

recreational users. Much of the hardrock leasing area burned in a wildfire in 2004 and soils and vegetation may be more susceptible

to impacts from motorized use.

In addition to changes in vegetation at exploration and mine sites and the network of roads and trails, establishment and

spread of non-native invasive plant species could occur, facilitated by motor vehicle use.

M.3.2.7 Visual Resources

Effects from Hardrock Mineral Leasing

Impacts from mineral leasing would be similar to the impacts from mining operations described in section 4.3.1.9 of the Eastern

Interior Draft RMP/EIS (BLM 2012a) which is incorporated by reference. Impacts from mining would vary depending on the methods

used and size of operation. Surface disturbing activities associated with mining, such as removal of vegetation and stockpiling

of materials, would impact line, form, color, and texture of mined areas creating contrast between mined areas and background

landforms. These activities may attract the attention of the casual observer. Large-scale placer mining would have the greatest

impact to visual resources. Small-scale placer mining would have similar impacts, but at a lesser scale. Suction dredging

would have the least impact, but would still impact visual resources due to camps and associated facilities.

Under Alternative D, 843,000 would be closed to hardrock mineral leasing, protecting visual resources in these areas (Figure

M.1). Closed areas include the Beaver Creek WSR Corridor, the Research Natural Areas, and approximately 86 percent of the

White Mountains NRA. This would protect visual resources by not allowing surface disturbing activities associated with mineral

development. The reclaimed areas along Nome Creek would be closed protecting the viewshed from the access road.

Approximately 16 percent of the NRA (160,000 acres) would be recommended open to hardrock mineral leasing. Two large-scale

and 11 small-scale placer mine operations are anticipated in this area. Total disturbance from all mechanized placer mining

is anticipated to be 507 acres over the life of the plan.

Approximately 11 suction dredge operations are anticipated. Each operation would have a camp with a footprint of one-half

acre over the life of the mine for a total maximum disturbance from all operations of 84 acres over the life of the plan.

The movement of materials from dredging occurs underwater and thus does not have a noticeable impact to visual resources and

is generally redistributed each spring during break-up or high water events. Impacts from the suction dredge camps are anticipated

to be less that six acres annually over the life of this plan.

Effects from Exploration Leasing and Licenses

Placer exploration activities would most likely occur within areas of medium development potential (85,000 acres). It is anticipated

that four exploration licenses could be issued over the life of the plan occurring on 5,000 acres each for a total of 20,000

acres (24 percent of the medium potential area). Each operation would have a disturbed annual footprint of 2.5 acres each

year for two years per license, for a total of 20 acres of disturbance.

Exploration licenses could be issued on up to 11,000 acres in the Roy Creek REE deposit; however, exploration activities would

disturb only an estimated 50 acres over the life of the plan.

Impacts to visual resources by exploration activities would depend on the scale of the action. Changes to line, form, color

and texture of the natural landscape would result from activities such as trenching, access trails, vegetation clearing for

drilling activities with the removal of vegetative cover and stockpiled materials creating form contrast between the trenched

areas and the stockpiled materials and the background landforms. Trenched material stockpiles would also create color contrast

between the greens of vegetation and the browns of soils. Texture would change from a natural medium, subtle texture of vegetation

to a course, rough contrast of disrupted soils and organic materials. Changes in line from the irregular, weak line of the

natural landscape to a regular, strong line between natural vegetation. Drill structures would introduce straight regular

lines into a natural irregular weak line of the natural landscape as well as color contrast between the greens of vegetation

and the drill structure for the short time the drill was in place.

M.3.2.8 Wildlife

Affected Environment

The hardrock mineral leasing area contains a high diversity of wildlife habitats ranging from lower-elevation riparian habitats

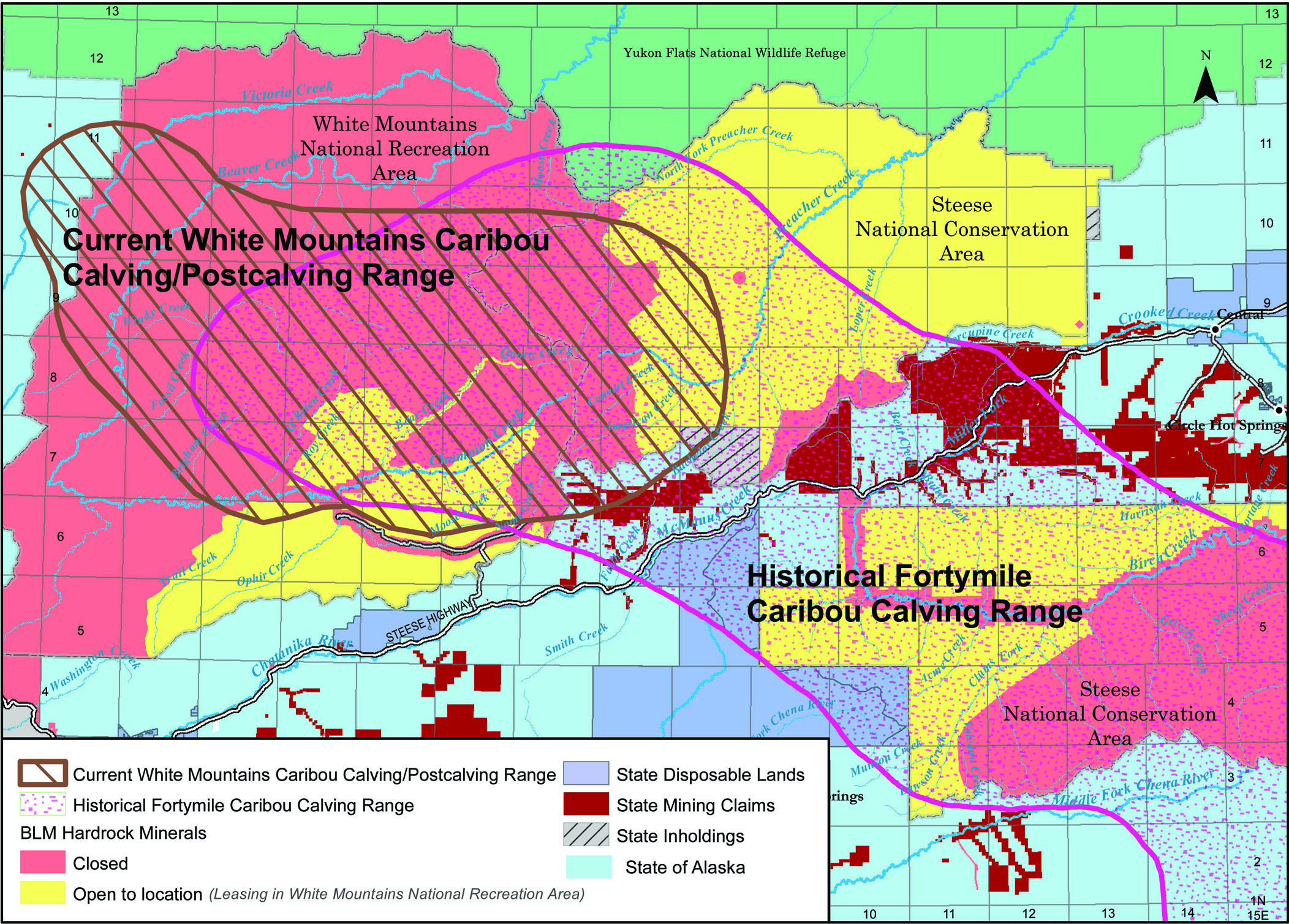

to alpine ridgelines. Most of the hardrock leasing area occurs within the historical calving area of the Fortymile caribou

herd and within the current concentrated calving and postcalving area of the White Mountains caribou herd (Figure M.3). The

presence of prehistoric archaeological sites immediately south of Nome Creek (Mile 57 of the Steese Highway) used for hunting

and caching of caribou during spring migration (Robin Mills pers. comm.) indicates that the area has long been used by large

numbers of caribou during calving and migration.

The northern portions of the hardrock leasing area (including the Roy Creek REE deposit and upper Bear Creek and Quartz Creek

placer gold areas) have been especially utilized by caribou. These areas occur within the core (most highly used) calving/postcalving

area of the White Mountains caribou herd and the area most highly used by the Fortymile caribou herd in the past. The Fortymile

herd calved in the White Mountains until 1963, and were reported to “most heavily” utilize the upper portions of Bear, Quartz,

and Champion creek drainages (Olson 1957), which are mostly within the hardrock leasing area. The “concentrated calving area”

identified by Olson (1957) centered on and included almost all of Bear and Champion creek drainages and headwater portions

of Moose and Nome creeks. The location of Fortymile herd calving shifted from year-to-year, but reports indicate that the

head of Bear Creek and Quartz Creek were the center of the herd’s long-term calving distribution.

Map of Caribou Habitat

This figure displays lands recommended open to hardrock mineral leasing in this Supplement or to location in Alternative D

of the Draft RMP/EIS relative to areas historically used by the Fortymile caribou herd as calving habitat and the current

White Mountains caribou herd calving/postcalving range. The core of the Fortymile calving range was roughly centered on the

heads of Bear and Quartz Creeks from the 1900s through the 1950s before shifting southeast towards the current calving range,

centered on southern Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve.

Dall sheep habitat occurs in and adjacent to northern portions of the hardrock mineral leasing area. A Dall sheep mineral

lick occurs 0.7 mile from the mineral leasing area in upper Little Champion Creek. The Roy Creek REE deposit is utilized by

Dall Sheep during the rutting season. Hobgood and Durtsche (1990) mapped the ridgeline in this area as rutting habitat. The

area was not included in a recent delineation of medium-to-high Dall sheep use based on a 2004-2008 study of radio-collared

Dall sheep, but that study did document short-term use by one ram during the rut, supporting the earlier designation. The

scattered granite tors on the ridge between Quartz, Champion, and Bear creeks are utilized by Dall sheep in all seasons. Although

not included in the area to be opened to leasing, this ridge is likely to be utilized for access to leases.

The hardrock mineral leasing area contains relatively high densities of moose, during at least the October through April time

period. Rut concentrations in the area were identified by Durtsche et al. (1990). High-quality riparian and aquatic habitats,

including salmon spawning and rearing and high densities of Arctic grayling, support aquatic and terrestrial wildlife species.

Nutrient transfer from aquatic to upland environments increases productivity of upland habitats. One known peregrine falcon

nest site occurs in the hardrock leasing area and a gyrfalcon nest site occurs adjacent to the hardrock leasing area. Redtail

hawk nest throughout the leasing area, often near streams.

Environmental Consequences

The effects on wildlife from mining (and exploration) of known deposits of hardrock minerals in the White Mountains Subunit

under mineral leases would be similar to those described for locatable mineral development elsewhere in the planning area

(BLM 2012a, section 4.3.1.12). Lease procedures (including Leasing Stipulations) allow the BLM to manage development of leases

so as to reduce impacts to a greater extent than management under the locatable mineral laws and regulations (43 CFR 3809),

but the nature and types of impacts would be similar.

Hardrock mineral leasing in Alternative D would result in an estimated direct disturbance from exploration and mining of 661

acres of terrestrial wildlife habitat. In addition, 20 miles of road is estimated to be built for access. Much of the surface

disturbance from mining and access would occur to riparian areas and wetlands habitats which are typically high-value wildlife

habitats. Effects of surface disturbance of these habitats would extend, to some extent, downstream into Beaver Creek WSR

(e.g., through effects on turbidity or fish migration). Human activities associated with mines would reduce use of riparian

habitats by many wildlife species in the immediate vicinity of the activity.

Changes in access and resulting increases in human use of the area may have a greater effect on wildlife and their habitats

than direct habitat disturbance from mining-related activities. Most of the leasing area is not accessible via existing trails

and much of the existing network of trails (mostly user-created) is susceptible to degradation from increased use. Mining

activities would require much heavier use than the current levels of use (much of which is related to hunting) and for longer

periods. Vehicles larger than allowed under OHV designations would be permitted in some cases, likely creating proportionally

greater disturbance. The linear amount of new access has not been determined, but if each of the estimated 29 suction dredge

and placer operations and exploration leases resulted in an average three miles of new trails (or seriously degraded existing

trail), about 87 miles of such new or seriously degraded trail might be predicted.

Winter overland moves would often require clearing of vegetation. The linear clearings created may lead to summer use by OHVs

and establishment of new OHV trails. The network of mining access trails would be utilized by lessees and recreationists to

reach previously inaccessible areas, within which additional new trails may be created, resulting in further expansion of

trail networks. Similarly, roads built for mine access would facilitate much greater OHV activity in the area in which they

are constructed. In general, motorized access would increase throughout the hardrock leasing area, especially in the high

potential areas. In addition to direct changes in habitat from user-created trails, the creation and use may also facilitate

the establishment and spread of invasive plants, especially in areas recently burned.

Although little Dall sheep habitat is within the identified hardrock leasing areas, human use of additional access to sheep

habitats in the Upper Champion Creek and Quartz Creek area may reduce sheep use of those habitats.

Moose may benefit from some ground disturbances that result in growth of deciduous browse species, such as willow. Increased

hunting pressure and harvest in previously remote areas would likely reduce harvest in areas with already-established access,

such as Nome Creek. Hunting pressure may result in some displacement of moose from high-density rutting areas.

Most of the estimated 661 acres of habitat disturbance would occur within the historical calving range of the Fortymile caribou

herd and current calving area of the White Mountains caribou herd (Figure M.3). The White Mountains caribou herd has a dispersed

calving distribution and the hardrock leasing area comprises a small proportion (11 percent) of the current White Mountains

caribou herd calving/postcalving area. The much larger Fortymile Herd calves in a dense distribution. More than half of the

hardrock leasing area of high development potential occurs within the area of concentrated calving identified by Olson (1957)

for the Fortymile herd in 1956. Exploration of the Roy Creek REE deposit is estimated to result in disturbance of 50 acres

of current and historic caribou calving habitat. Exploration activities would be required to occur outside of calving/postcalving

season in this area, limiting impacts from those activities. The greatest impact to caribou would likely be the change in

access, human infrastructure, and the generally increased levels of human activity in the area. Although anticipated placer

gold mining operations in the area may have little direct effect on caribou use of the area, the combined direct and indirect

effects from changes in access and human use patterns in the area would likely reduce the suitability of the area as calving

habitat and potentially reduce the likelihood that the Fortymile Herd would reestablish a habit of calving season use of the

White Mountains. The overall level of disturbance, including linear disturbance, and human activity within the calving area

would influence the likelihood of use by caribou.

Compared with other large migratory caribou herds, the Fortymile herd’s current annual range has a low proportion of range

above treeline (17 percent; Boertje et al. in press). Boertje and others (in press) surmised that overgrazing of the herd’s

current core upland tundra habitat may have resulted in reduced herd nutrition levels and suggested that expansion to additional

spring and summer upland tundra in the White Mountains may be of key importance to realizing continued herd growth.

Several species of migratory birds are dependent on (or found in much higher densities in) riparian habitats. Placer mining

would remove habitat for these species in localized areas and habitat recovery may require several decades. Regardless of

when the vegetation clearing occurs, impacts from the changes in vegetation would persist probably for many years. ROPs (Appendix

A) protect only currently nesting birds. Nesting peregrine falcon and gyrfalcon are more likely to be affected indirectly

by changes in access than directly by mining activities. Nesting redtail hawk may be displaced by nearby placer mining and

dredging activities. These impacts are not expected to result in planning area population level declines of any species of

migratory birds.

Cumulative Effects

Hardrock mineral leasing in Alternative D would add to the cumulative impacts from exploration and development of locatable

and leasable minerals elsewhere in the planning area, including on state and private lands.